Is the cooling off period in HMA Mandatory or directory: Analysis with the Amardeep Singh v/s Harveen Kaur

Amardeep Singh Vs Harveen Kaur, AIR 2017 SC 4417

Facts- The Appellant (Amardeep Singh) married the Respondent on January 16, 2001. (Harveen Kaur). Two children were born out of wedlock in 1995 and 2003, respectively. As a result of their disagreements, the couple has been living separately since 2008.

- Finally, on April 28, 2017, a settlement was reached, and the parties agreed to seek divorce by mutual consent because there was no possibility of reconciliation remaining. The appellant granted the wife permanent alimony in the amount of Rs 2.75 crore.

- The appellant dutifully honoured two cheques totaling Rs. 50,00,000 in favour of the wife. The appellant was in charge of the children's custody.

- The Appellant filed a plea with the Tis Hazari Court's Family Court in New Delhi, requesting that the court give a divorce judgement based on mutual consent. Furthermore, both parties' statements were recorded.

- Following that, both parties to the case sought for a six-month delay in the second motion, claiming that they had been living apart for more than eight years and that there is no possibility of reconciliation.

- The parties argued in this petition before the Hon'ble Supreme Court that the six-month statutory period for the second motion should be shortened in light of the supreme Court's past judgements in the case.

Equivalent Citation: 2017 (8) SCC 746; 2017 (9) JT 106

Case no: Civil Appeal no. 11158 of 2017 (Arising out of Special Leave Petition No. 20184 of 2017)

Case Type: Civil Appeal.

Petitioner: Amardeep Singh

Respondent: Harveen Kaur

Bench: Uday Umesh Lalit, Adarsh Kumar Goel, Hon'ble J.J.

Issues

- Whether the period of six months prescribed under Sec 13-B(2) of the HMA was mandatory period or it could be waived off under certain circumstances by the court?

- Whether it is appropriate to use Article 142 of the Constitution to waive the statutory term set forth in Section 13B(2) of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955?

Marriage is seen as a sacred alliance for life, it is not merely a relationship between two people, but also between two families. Nonetheless, it is a relationship between two individuals, and because no human being is flawless, it is quite likely that two people will not feel compatible enough to live together for the rest of their lives.

The consent theory of divorce is based on the reasoning that freedom that the parties to marriage enjoy for entering in the marriage should be the same to dissolve the marriage. Continuing of a marriage where both the parties lack compatibility would not only result in impacting the parties but also become a breeding place for aberrant and delinquent children. [1]

The very substance of marriage is Mutual fidelity and if due to any reason the parties to marriage feel that such fidelity can only be preserved by dissolution, such dissolution would prevent chaos and make the divorce between the parties' trouble free and inexpensive. [2]

The Hindu Marriage Act recognises this concept through the provision of Section 13-B[3] of the Hindu Marriage Act and Section 28 of the Special Marriage Act known as provisions relating to divorce by mutual concept.

In the present case the parties filed a divorce under Section 13-B of the Hindu Marriage Act,1955 which deals with the Divorce by mutual consent.

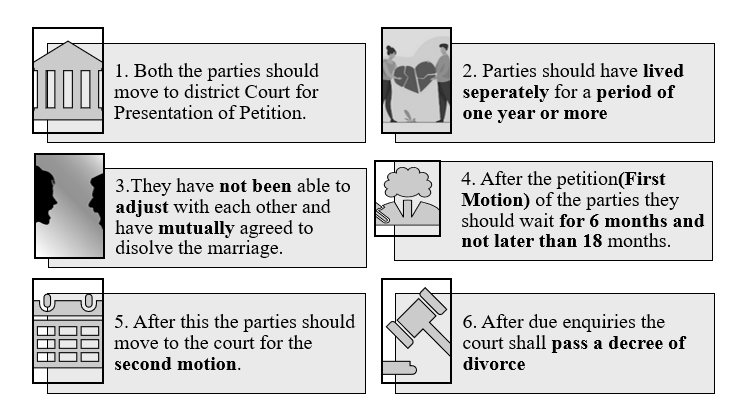

The essentials of the said provision is:

In the present case the lower courts had already decided on the fact that there

was no chance of rehabilitation as both had been living separately since 2008,

also the question of alimony and custody was also decided. The parties in the

present case moved to the Apex court in order to waive of the minimum six-month

cooling period between the first and the second motion.

Before deciding on the question that whether the cooling period can be waived

off, it is essential to analyse the position of the courts in deciding over

matters relating to personal laws or passing decisions in its exercise of the

Article 142[4] which are in contravention with any statutory provisions.

Judicial approach on the given issue in previous judgments of Courts

Before this Judgement there was a conflicting opinion on by Supreme Court on

waiving of the cooling period in matters related to divorce, which is discussed

below:

In a catena of cases [5]it has been held by the Supreme Court that no court has

the authority to issue a direction or order an authority to act in contravention

to a statutory provision. The purpose of the courts is to enforce the rule of

law, not to issue orders or directions that are contradictory to law.

The same

was held in Manish Goel vs Rohini Goel[6] where the court while deciding on the

fact that cooling off period should be waived off or not, in addition to this a

constitution bench in Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr[7] stated that while

exercising of the Article 142 of the Constitution to do complete justice to the

parties the courts must not only consider the consistency of the order with the

fundamental rights but should also take in account the substantive provisions of

the relevant statutory provisions in question.

It should be understood that the

courts cannot pass any order under Article 142 which is against the procedure

established in the said statutory provision as it would lack a basis on which

such a decision can be concluded.[8]

However, it is pertinent to note that that power under Article 142 had been

exercised in cases where the Court found the marriage to be totally unworkable,

emotionally dead, beyond salvage and broken down irretrievably parties and the

article was used to prevent further agony to the parties. In addition to this,

the Supreme Court without taking in consideration the above-stated judgements

had passed a decision Nikhil Kumar vs. Rupali Kumar, [9]in which the cooling-off

period of 6 months was waived by the Court under Article 142[10] of the

Constitution and the divorce was granted to the husband and wife.

Court's decision

In order to remove the conundrum between the two conflicting views, the court

upheld the decision in Manish Goel[11] and explained that decision of the Apex

Court in Manish Goel decision was not considered while waiving off the cooling

period in the previous and judgements and the power under Article 142 cannot be

exercised if it is in contrivance to a substantive Statutory provision

especially when no proceedings are pending before the court for the purpose of

waiver of the Statute.

However, the court also analysed the legislative intent of Section 13-B(2) to

understand whether the provision was compulsory or directory in nature.

As a result, if the circumstances of the case necessitate it and there is no

hope of reconciliation between the parties, the courts have been increasingly

ready to waive this term.

Analysis

Marriage was regarded as a samskar (sacrament), a religious requirement, and

thus indissoluble in Hindu law. For almost two thousand years, shastric law and

Hindu society were unaware of divorce. Divorce was the exception rather than the

rule, and acceptance was based on custom and exception.

The correlation between

law and society is of paramount importance. [12]A matrimonial alliance plays a

crucial role in a country's societal setup.[13] Under traditional Hindu law, as

it existed previous to the statutory law on the subject, and it could not be

dissolved by consent. However, as a result of the influence of western ideas,

some laws were progressively enacted in some areas.

It was due to this westernisation that the concept of divorce by mutual consent was introduced by

the way of amendment of 1976 which prohibited a divorce from being granted until

six months have passed, the motive of such period was to allow the parties to

reconsider their positions so that the court will only grant a divorce by mutual

consent if there is no hope of reconciliation.

The purpose of the clause is to allow the parties to consent to the dissolution

of a marriage if it has irreversibly broken down and to allow them to

rehabilitate the marriage using available choices. The modification was

motivated by the belief that the forcible continuation of marriage status

between unwilling couples served no purpose. The purpose of the cooling-off

period was to prevent a hasty judgement if there was a chance that conflicts may

be resolved otherwise.

The goal was not to prolong a meaningless marriage or the

suffering of the parties when there was no hope of reunion. Despite the fact

that every attempt should be made to save a marriage, in cases where there are

no chances of reconciliation, the court should be powerless in enabling the

parties to have a better option.

It was held in Grandhi Venkata Chitti Abbai [14]that reading of Section 13-B

(2) as obligatory would undermine the fundamental goal of liberalising the

policy of decree of divorce by mutual consent especially when the parties have

been living separately for a significant period of time, and it has been held by

the court that the waiting period is merely advisory in nature[15] and the aim

and object of the provision is to provide time for the parties to reflect and

reconcile.[16]

The court explained that in order to determine whether a provision is mandatory

or directory, language alone is not always decisive but the subject matter of

the provision must also be taken into account. The court laid down that in the

current scenario even with the analysis of a plethora of cases, no universal

rule can be construed in determining whether mandatory enactments shall be

considered directory only or obligatory with an implied nullification for

disobedience and in such cases it becomes essential for court to analyse the

real intention of the legislature.

For doing so the court should not only

consider:

- The nature and design of the statute

- The consequences which would follow from construing it the one way or the other;

- The impact of other provisions whereby the necessity of complying with the provisions in question is avoided

- The circumstances, namely, that the statute provides for a contingency of the non-compliance with the provisions;

- The fact that the non-compliance with the provisions is or is not visited by some penalty; the serious or the trivial consequences,

Mandatory provision

Discretionary provision

Object of the enactment defeated by construction = Mandatory provision

If holding mandatory causes general inconvenience to innocent person without furthering the interests of the object of the enactment = Directory provision

By applying the rules of interpretation in provision 13-B(2), one can note that if the said provision is made mandatory it would cause inconvenience and agony to the parties involved from furthering their interests as noted in the present case. Thereby the court laid down certain conditions for the courts to consider while waiving the cooling-off period and making the said provision directory in nature.

These conditions are:

- The statutory period of six months specified in Section 13B(2), in addition to the statutory period of one year under Section 13B(1) of separation of parties is already over before the first motion itself;

- All efforts for mediation/conciliation including efforts to reunite the parties have failed and there is no likelihood of success in that direction by any further efforts;

- The parties have genuinely settled their differences including alimony, custody of child or any other pending issues between the parties;

- The waiting period will only prolong their agony.

Since in the present case there were the parties had already been living apart since 2008 and there was no chance of reconciliation and all the possible alternatives for solving the marriage had already been exhausted and the question of custody and maintenance had already been decided the said case formed as a special case where the provision could be considered directory and hence cooling of the period could be waived off.

Conclusion and Recommendations

While the decision made by the court was appropriate and crisp, the author believes that the court that certain amendments could be made to prevent the misuse of the law. The author would make a few recommendations in this respect:

- The Marriage Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2010 which had extensively drafted

the law to be included under Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act should be

passed. It included a new sub-section to be included which read couple with

a few other provisions for the safeguard of misuse of this provision.

The bill was stuck and did not pass and therefore the law was not amended. This bill was a fresh step towards introducing an irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground for divorce. The Bill included provisions for easing the process of divorce by defining the period of time husband and wife have been living apart as well as the amendment also explained divorce on the grounds that the marriage has broken down irretrievably.

- The Author believes that the directory power of waiving of the cooling period should be used by the courts in only special and limited circumstances and the object and the intention of the waiting period i.e., to allow the parties to the marriage to rethink their decision for reconciliation should be kept intact.

Authorities Cited:

Cases:

- Dinesh Kumar Shukla v Neeta AIR 1999 AP 9...........................................................9

- Hitesh Narendra Doshi v Jesal Hitesh Joshi AIR 2000 AP 36......................................9

- Karnataka SRTC v. Ashrafulla Khan [(2002) 2 SC 560.............................................6

- Manish Goel vs Rohini Goel 1 (2016) 13 SCC 383....................................................7

- Nikhil Kumar vs. Rupali Kumar (2009) 10 SCC 41...................................................7

- Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr[AIR 1963 SCC 996..........................................7

- Rajaram v. Union of India [(2001) 2 SCC 186..........................................................7

- State of Punjab v. Renuka Singla[(1994) 1 SCC 175],..............................................6

- State of U.P. v. Harish Chandra [(1996) 9 SCC 309],..............................................6

- Union of India v. Kirloskar Pneumatic Co. Ltd. [(1996) 4 SCC 453]........................6

- University of Allahabad v. Dr. Anand Prakash Mishra [(1997) 10 SCC 264] ;......... 6

- Hindu Marriage (Amendment)Act § 13-B No. 68, Acts of Parliament, 1976 (IND).... 5

- India Const. Art. 142........ 6

- Mayne, Hindu Law 101 (11th ed. 1953); 1 Cambridge History of India , 88; Kane, 2 History of Hindu D haram Shas tras 427 (Pa...... 8

- Dr.Pawan Diwan Modern Hindu Law (170-175) 8th Edtn................ 5

- Raj Kumari Agrawala Changing Basis Of Divorce And The Hindu Law Vol. 14, No. 3 (July-September 1972), pp. 431-442 (12 pages) Journal of the Indian Law Institute..... 8

- Vesey-FitzGerald The Projected Codification of Hindu Law Vol. 29, No. 3/4 (1947), pp. 19-32 (14 pages)........... 5

- Constitution of India, 1949; Article 142

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955; Sections 13B(1) & 13B(2)

- Dr.Pawan Diwan Modern Hindu Law (170-175) 8th Edtn.

- S. Vesey-FitzGerald The Projected Codification of Hindu Law Vol. 29, No. 3/4 (1947), pp. 19-32 (14 pages) Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law https://www.jstor.org/stable/755065

- Hindu Marriage (Amendment)Act § 13-B No. 68, Acts of Parliament, 1976 (IND)

- India Const. Art. 142

- State of Punjab v. Renuka Singla[(1994) 1 SCC 175], State of U.P. v. Harish Chandra [(1996) 9 SCC 309], Union of India v. Kirloskar Pneumatic Co. Ltd. [(1996) 4 SCC 453], University of Allahabad v. Dr. Anand Prakash Mishra [(1997) 10 SCC 264] ; Karnataka SRTC v. Ashrafulla Khan [(2002) 2 SC 560]

- Manish Goel vs Rohini Goel 1 (2016) 13 SCC 383

- Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr[AIR 1963 SCC 996]

- Rajaram v. Union of India [(2001) 2 SCC 186]

- Nikhil Kumar vs. Rupali Kumar (2009) 10 SCC 415

- India Const. Art. 142

- Supra 6

- Raj Kumari Agrawala Changing Basis Of Divorce And The Hindu Law Vol. 14, No. 3 (July-September 1972), pp. 431-442 (12 pages) Journal of the Indian Law Institute https://shibbolethsp.jstor.org/start?entityID=https%3A%2F%2Fidp.siu.edu.in%2Fopenathens&dest=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43950149&site=jstor

- Mayne, Hindu Law 101 (11th ed. 1953); 1 Cambridge History of India , 88; Kane, 2 History of Hindu D haram Shas tras 427 (Par

- Grandhi Venkata Chitti Abbai AIR 1999 AP 91

- Dinesh Kumar Shukla v Neeta AIR 1999 AP 91

- Hitesh Narendra Doshi v Jesal Hitesh Joshi AIR 2000 AP 364

Law Article in India

Lawyers in India - Search By City

Popular Articles

How To File For Mutual Divorce In Delhi

How To File For Mutual Divorce In Delhi Mutual Consent Divorce is the Simplest Way to Obtain a D...

Increased Age For Girls Marriage

It is hoped that the Prohibition of Child Marriage (Amendment) Bill, 2021, which intends to inc...

Facade of Social Media

One may very easily get absorbed in the lives of others as one scrolls through a Facebook news ...

Section 482 CrPc - Quashing Of FIR: Guid...

The Inherent power under Section 482 in The Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (37th Chapter of t...

Home | Lawyers | Events | Editorial Team | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Law Books | RSS Feeds | Contact Us

Legal Service India.com is Copyrighted under the Registrar of Copyright Act (Govt of India) © 2000-2026

ISBN No: 978-81-928510-0-6

Please Drop Your Comments