Paris Agreement Success on Climate Change

The international community, which included 195 countries, reached an agreement

at the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which took place in Paris,

France, from November 30 to December 11, 2015. Participants and the media have

welcomed the agreement as a major policy turning point in the fight against

human-caused climate change.

The following is a brief critical analysis in which I explain why the Paris Agreement makes no difference. I discuss how the Agreement was obtained by omitting practically all fundamental problems related to the causes of human-caused climate change and by providing no specific plans of action. Instead of making significant reductions in carbon and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as soon as possible, the promisers objectives promise an increase in damages and see worst-case scenarios as a 50:50 likelihood.

The Paris Agreement represents a commitment to long-term economic expansion, risk management over disaster prevention, and the role of future inventions and technology as a saviour. The international community's principal commitment is to maintain the current social and economic structure. As a result, there is a scepticism that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is incompatible with long-term economic growth.

The reality is that nation states and transnational businesses are expanding fossil fuel energy exploration, extraction, and combustion, as well as accompanying infrastructure for production and consumption, at an unstoppable pace. The Paris Agreement's goals and pledges have little to do with biophysical, social, or economic reality.

Introduction

The Paris Agreement as part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Development Agenda made 2015 a memorable year for the international community. With 17 goals and 169 targets that apply to both developing and developed countries, the SDGs aim to alter the world by assuring human well-being, economic prosperity, and environmental protection at the same time (United Nations General Assembly, 2015).

Similarly, the Paris Agreement unites all nations, industrialised and developing, in a common cause to reduce global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius, relative to pre-industrial levels (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015). One of the most notable accomplishments is that it links between development and climate change are clearly stated in each publication.

This decision was made in awareness of the fact that development and climate change must be tackled concurrently in order to avoid adverse tradeoffs and high costs, particularly for developing nations, as well as to maximise the benefits of establishing these ties.

Many researchers, on the other hand, are concerned about the Paris agreement possible incompatibility, particularly the incompatibility of socioeconomic progress and environmental sustainability (International Council for Science and International Social Science Council, 2015). Numerous studies, in particular, have discussed the conflict between the SDGs' sustainability and growth goals (Hickel, 2019).

The SDGs, according to Gupta and Vegelin (2016), represent "tradeoffs in favour of economic growth over social well-being and ecological viability." The fact that some SDG metrics are highly connected with GNI per capita supports these assertions.

There is tension among private sector for implementation of sayings of Paris agreement and SDG. There are arguments like business is neither a superhero or a "magic bullet" (McEwan, Mawdsley, Banks, & Scheyvens, 2017) that it can give economic strength and climate control simultaneously. Developing countries still have a long way to go before modernisation, they would face greater challenges than developed countries if pursuing economic growth through various policy measures, such as private sector development, inevitably leads to increased energy demands and CO2 emissions (Han & Chatterjee, 1997).

The link between economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions has been the subject of several studies. Previous empirical research strongly suggest that economic development plays a role in the nexus between economic growth and environmental protection (Tiba & Omri, 2017). Implementing the Paris agreement would necessitate compromise in terms of CO2 emissions mitigation if the Paris agreement strongly incorporate growth ambitions, which ultimately lead to higher CO2 emissions. In contrast, if too strict emission reduction measures are implemented, poverty reduction may be slowed relative to the reference scenario.

To understand whether trade-off genuinely exists between overall SDG development and CO2 emissions change for different nations are needed to understand. However, almost no research of this nature has ever been done previously.

The article offers light on expectations for the countries in achieving the Paris agreement success and reducing CO2 emissions at the same time and whether it would be possible or not.

List of Abbreviations:

Legal Framework

The 2015 Paris Agreement is described as a "legally enforceable international pact on climate change" by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

However, the agreement has caused several famous experts to contend that the Paris Agreement is not, in fact, a legally binding treaty.

The Paris Understanding's power is based on a fluid pact about the repercussions of breaking an international agreement that isn't fully defined.

The Paris Agreement, the 27-page agreement that set the parameters for the climate talks at COP26, has been dogged by one question for a long time: Is it legally enforceable?

The 2015 Paris Agreement is described as a "legally enforceable international pact on climate change" by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. However, the treaty itself has limited legal enforce. It does not impose penalties for parties who break its provisions, such as fees or embargo, and there is no international court or regulating authority to ensure compliance. As a result, some famous experts have argued that the Paris Agreement is not, in fact, a legally enforceable instrument.

Arizona State University law professor Daniel Brodansky disagrees. He noted in Receil, an environmental legal journal, in 2016 that the binary argument obscures a more nuanced fact. While nations (and other jurisdictions) can establish clear norms about the legal authority of contacts within their borders, international law is less clear. Agreements enforceability is based on a shared understanding of what a legal bond signifies in the global community.

Is there any part of the Paris Agreement that is genuinely legally binding?

The subject of how legal and enforceable the Paris Agreement may be was hotly disputed when it was being drafted by global delegates from potential member countries. The US, for example, could not be held responsible for specific results if it backed the deal. If it had, former President Barack Obama would have needed the support of two-thirds of the US Senate, which was dominated at the time by Republican members opposed to the pact.

Instead, treaty negotiators made an ingenious concession: they chose to make the treaty's required processes legally enforceable rather than the responsibility to fulfil predetermined goals. That is, the agreement legally binds countries to develop and revise nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the collective effort to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius, for example. It also requires that they meet and report on their progress at international conferences like as COP26.

Analysis

The following is a brief critical analysis in which I explain why the Paris Agreement makes no difference. I discuss how the Agreement was obtained by omitting practically all fundamental problems related to the causes of human-caused climate change and by providing no specific plans of action. Instead of making significant reductions in carbon and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as soon as possible, the promisers objectives promise an increase in damages and see worst-case scenarios as a 50:50 likelihood.

The Paris Agreement represents a commitment to long-term economic expansion, risk management over disaster prevention, and the role of future inventions and technology as a saviour. The international community's principal commitment is to maintain the current social and economic structure. As a result, there is a scepticism that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is incompatible with long-term economic growth.

The reality is that nation states and transnational businesses are expanding fossil fuel energy exploration, extraction, and combustion, as well as accompanying infrastructure for production and consumption, at an unstoppable pace. The Paris Agreement's goals and pledges have little to do with biophysical, social, or economic reality.

Introduction

The Paris Agreement as part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Development Agenda made 2015 a memorable year for the international community. With 17 goals and 169 targets that apply to both developing and developed countries, the SDGs aim to alter the world by assuring human well-being, economic prosperity, and environmental protection at the same time (United Nations General Assembly, 2015).

Similarly, the Paris Agreement unites all nations, industrialised and developing, in a common cause to reduce global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees Celsius, relative to pre-industrial levels (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015). One of the most notable accomplishments is that it links between development and climate change are clearly stated in each publication.

This decision was made in awareness of the fact that development and climate change must be tackled concurrently in order to avoid adverse tradeoffs and high costs, particularly for developing nations, as well as to maximise the benefits of establishing these ties.

Many researchers, on the other hand, are concerned about the Paris agreement possible incompatibility, particularly the incompatibility of socioeconomic progress and environmental sustainability (International Council for Science and International Social Science Council, 2015). Numerous studies, in particular, have discussed the conflict between the SDGs' sustainability and growth goals (Hickel, 2019).

The SDGs, according to Gupta and Vegelin (2016), represent "tradeoffs in favour of economic growth over social well-being and ecological viability." The fact that some SDG metrics are highly connected with GNI per capita supports these assertions.

There is tension among private sector for implementation of sayings of Paris agreement and SDG. There are arguments like business is neither a superhero or a "magic bullet" (McEwan, Mawdsley, Banks, & Scheyvens, 2017) that it can give economic strength and climate control simultaneously. Developing countries still have a long way to go before modernisation, they would face greater challenges than developed countries if pursuing economic growth through various policy measures, such as private sector development, inevitably leads to increased energy demands and CO2 emissions (Han & Chatterjee, 1997).

The link between economic growth, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions has been the subject of several studies. Previous empirical research strongly suggest that economic development plays a role in the nexus between economic growth and environmental protection (Tiba & Omri, 2017). Implementing the Paris agreement would necessitate compromise in terms of CO2 emissions mitigation if the Paris agreement strongly incorporate growth ambitions, which ultimately lead to higher CO2 emissions. In contrast, if too strict emission reduction measures are implemented, poverty reduction may be slowed relative to the reference scenario.

To understand whether trade-off genuinely exists between overall SDG development and CO2 emissions change for different nations are needed to understand. However, almost no research of this nature has ever been done previously.

The article offers light on expectations for the countries in achieving the Paris agreement success and reducing CO2 emissions at the same time and whether it would be possible or not.

List of Abbreviations:

- UNFCCC - United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- The Convention - United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- COP - Conference of Parties

- SDG - Sustainable Development Goals

- NDC - National Determined Contributions

Legal Framework

The 2015 Paris Agreement is described as a "legally enforceable international pact on climate change" by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

However, the agreement has caused several famous experts to contend that the Paris Agreement is not, in fact, a legally binding treaty.

The Paris Understanding's power is based on a fluid pact about the repercussions of breaking an international agreement that isn't fully defined.

The Paris Agreement, the 27-page agreement that set the parameters for the climate talks at COP26, has been dogged by one question for a long time: Is it legally enforceable?

The 2015 Paris Agreement is described as a "legally enforceable international pact on climate change" by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. However, the treaty itself has limited legal enforce. It does not impose penalties for parties who break its provisions, such as fees or embargo, and there is no international court or regulating authority to ensure compliance. As a result, some famous experts have argued that the Paris Agreement is not, in fact, a legally enforceable instrument.

Arizona State University law professor Daniel Brodansky disagrees. He noted in Receil, an environmental legal journal, in 2016 that the binary argument obscures a more nuanced fact. While nations (and other jurisdictions) can establish clear norms about the legal authority of contacts within their borders, international law is less clear. Agreements enforceability is based on a shared understanding of what a legal bond signifies in the global community.

Is there any part of the Paris Agreement that is genuinely legally binding?

The subject of how legal and enforceable the Paris Agreement may be was hotly disputed when it was being drafted by global delegates from potential member countries. The US, for example, could not be held responsible for specific results if it backed the deal. If it had, former President Barack Obama would have needed the support of two-thirds of the US Senate, which was dominated at the time by Republican members opposed to the pact.

Instead, treaty negotiators made an ingenious concession: they chose to make the treaty's required processes legally enforceable rather than the responsibility to fulfil predetermined goals. That is, the agreement legally binds countries to develop and revise nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the collective effort to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius, for example. It also requires that they meet and report on their progress at international conferences like as COP26.

Analysis

- The Good: Climate change policy is making a comeback.

The time leading up to the signing of the Paris Agreement gave the multilateral process of creating a worldwide approach to climate change mitigation and adaptation a much-needed boost. At the start of the summit, unprecedented participation by world leaders, including President Barack Obama, Chinese President Xi Jinping, and other heads of state, helped set the tone, allowing national delegations to make the necessary compromises.

As a result, the text now includes a new collective goal of "keeping global average temperature increases well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to restrict temperature increases to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels" (Article 2).

The Paris Agreement's near-universal involvement and acceptance of responsibility is a big positive. This is a significant improvement from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which only demanded mitigation action from a small number of industrial countries that accounted for the majority of historical emissions.

- The bad: Uncontrollable and erratic

The Paris Agreement established a new, and largely concerning, form of government voluntary "nationally decided contributions." Many of the outcomes are predicted to be driven by market forces and yet to be commercialized innovative technologies, with international leaders cheering the transformation on.

Many significant players, including the United States, China, and India, are interested in this new form of voluntary national actions for various reasons. However, it places the future schedule for actual emission reductions in the hands of the world's biggest polluters, with no collective framework in place to ensure that individual countries fulfil specific targets.

The system's success is overly reliant on the good will of international leaders. Many national politicians who spent political capital in making the Paris Agreement a reality are no longer in government to oversee even initial implementation - for example, US President Barack Obama is not in office to do so. It is difficult to predict the sustained interest of those who have replaced them.

- Which countries are responsible for climate change?

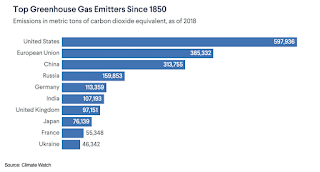

Developing countries contend that, over time, affluent countries have released more greenhouse gases. They argue that because they were allowed to grow their economies without restraint, these wealthy countries should now shoulder a greater share of the responsibility. Indeed, the US has produced the greatest emissions of all time, followed by the European Union (EU).

China and India, along with the United States, are now among the world's top annual emitters. Developed countries have argued that they must act sooner rather than later to combat climate change.

Major climate agreements have evolved in how they target carbon reductions in the midst of this discussion. Only rich countries were expected to reduce emissions under the Kyoto Protocol, whereas the Paris Agreement recognised climate change as a global issue and compelled all countries to establish emissions targets.

Law Article in India

Lawyers in India - Search By City

Popular Articles

How To File For Mutual Divorce In Delhi

How To File For Mutual Divorce In Delhi Mutual Consent Divorce is the Simplest Way to Obtain a D...

Increased Age For Girls Marriage

It is hoped that the Prohibition of Child Marriage (Amendment) Bill, 2021, which intends to inc...

Facade of Social Media

One may very easily get absorbed in the lives of others as one scrolls through a Facebook news ...

Section 482 CrPc - Quashing Of FIR: Guid...

The Inherent power under Section 482 in The Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (37th Chapter of t...

Home | Lawyers | Events | Editorial Team | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Law Books | RSS Feeds | Contact Us

Legal Service India.com is Copyrighted under the Registrar of Copyright Act (Govt of India) © 2000-2026

ISBN No: 978-81-928510-0-6

Please Drop Your Comments