Impact Of World Trade Organization On Indian Trade

India has been a member of the WTO since its inception in 1995. WTO is sometimes

referred to as the 'free trade' institution seeking to

promote multilateralism and a rule-based system in the conduct of global trade

amongst countries. India is one of the founding members of WTO along with more

than 130 other countries. Economists believe that India's participation in an

increasingly rule-based system in the governance of international trade would

eventually lead to better prosperity for the nation.

Various trade disputes of India with other nations have been settled through WTO. India has also played an important part in the effective formulation of major trade policies. By being a member of WTO, several countries are now trading with India, thus giving a boost to production, employment, the standard of living and an opportunity to maximize the use of the world resources.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) as an institution has perhaps never come under as much of a siege as now. Increasing protectionism, inadequate judges in the Appellate Tribunal for dispute resolution, increasing number of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) etc. have resulted in member countries questioning the efficacy of WTO as an institution meant to ensure free trade and promote multilateralism. Apart from the ongoing trade war-like situation between USA and China, there have been trading skirmishes across the globe.

India (along with a few other developing countries) has and continues to have objections (raised and ventilated through WTO Forums) on issues like agriculture especially subsidies in the context of food security etc. and trade facilitation.

India has consistently taken the stand that the launch of any new round of talks depends on a full convergence of views amongst the entire WTO membership on the scope and framework for such negotiations. India's more urgent task is to resolve the concerns of developing countries on the implementation of the Uruguay Round agreements. India is against calls for new commitments from the developing world for achieving symmetry and equity in the existing agreements. It is in favour of non-trade issues being permanently kept off the negotiating table.

Ensuring food and livelihood security is critical, particularly for a largely agrarian economy like India. India's proposal in ongoing negotiations includes suggestions like allowing developing countries to maintain an appropriate level of tariff bindings, commensurate with their developmental needs and the prevailing distortions in international markets.

India is also seeking a separate safeguard mechanism including provision for imposition of quantitative restrictions under specified circumstances, particularly in case of a surge in imports or decline in prices; exemptions for developing countries from obligations to provide minimum market access; exemptions of all measures taken by developing countries for poverty alleviation, rural development and rural employment.

India's immediate priority is that the agreements reached earlier with the developing countries should be implemented to correct inherent imbalances in some of the Uruguay Round agreements. Sincere and meaningful implementation of commitments undertaken by developed countries and operationalization of all special and differential treatment clauses for developing countries in the various agreements is made.

India also strongly favourthe extension of higher levels of protection to the geographical indications for products like Basmati rice, Darjeeling tea, and Alphonso mangoes at par with that provided to wines and spirits under the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. In the TRIMS (Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures) review India wants flexibility for developing countries in adopting appropriate domestic policy while permitting foreign investment.

Developed countries are pushing for a comprehensive agenda like rules on investment, environment, competition policy, trade facilitation, transparency in government procurement, labour standards etc. They are pressing for incorporating non-trade issues of environment and labour standards.

Using as an excuse that the production of products in developing countries are not being done under proper environmental and labour standards, they can ban the imports of their products or impose other non-tariff restrictions. The developing countries are opposed to these non-trade issues.

Some critics of WTO have expressed their fears that Indian farmers are threatened by the WTO. There is however no adverse impact. India has bound its tariff to the extent of 100 per cent for primary agricultural products, 150 per cent for processed agricultural products and 300 per cent for edible oils. A few agricultural products had been bound historically at low levels but these bindings have been raised following the Article XXVIII negotiations held in this regard.

It has also been possible to maintain without hindrance the domestic policy instruments for the promotion of agriculture or targeted supply of food grains. Domestic policy measures like the operation of minimum support price, public distribution system as well as provision of input subsidies to agriculture have not in any way been constrained by the WTO agreement.

Certain provisions in the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) also give us the flexibility to provide support for research, pest and disease control, marketing and promotion services, infrastructure development, payments for relief from natural disasters, payments under the regional assistance programmes for disadvantaged regions and payments under environmental programmes. Indian farmers now need to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the AoA, by addressing productivity issues and making their products more competitive globally.

India (along with a few other developing countries) has and continues to have objections (raised and ventilated through WTO Forums) on issues like agriculture especially subsidies in the context of food security etc. and trade facilitation.

India has been pushing agricultural issues at the WTO. Public stock holding (which includes purchasing, stockpiling and distributing food by Governments in times of necessity) is very important for India's food security. While stockpiling and distributing are as per WTO guidelines, the purchasing of food by governments at a price higher than the market price is considered by the WTO as a trade-distorting subsidy.

The 11th Ministerial Conference held in Buenos Aires in 2017 did not result in any permanent solution to the issue of public stock holding. India has been a votary of a permanent solution to the issue of stock holding. The sticking point in this issue, as far as India is concerned, has been how the Minimum Support Price (MSP) (MSP is the guaranteed price fixed by the Government of India and paid to the farmers for their produce. It is essentially a support mechanism extended by the Government to the farmers to ensure that the farmers get a minimum profit for their products especially when prices in the open market are less than the costs incurred) is fixed.

According to the WTO's Agreement on Agriculture, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) would have to be calculated based onthe price of food grains in 1986-88 and the total subsidy would have to be below 10 per cent of the total value of production. India has strongly disputed this formula because the current prices are much higher and hence the total MSP given as subsidy would also be higher. Countries like India and China have opposed the huge production-related price distorting subsidies given by the developed countries like the US and the EU to their farmers. The US alone gives around USD 150 billion in direct subsidies to farmers.

Indian industry has had to face greater competition in the wake of globalisation. But it has completed, as can be inferred from the fact that there has been no particular surge in imports. In fact, as per the provisional data for 2000-01, non-oil imports declined by 14 per cent whileexports rose by over 20 per cent in the same period. A close watch is also being kept to ensure that Indian industry does not have to face unfair competition from dumped or subsidised imports of other countries.

As for drug prices, safeguards are provided like compulsory licensing, price controls, and parallel imports which should help address this concern. It must also be recognised that the prices of medicines are influenced by several factors including the level of competition, size of the market, purchasing capacity etc.

The issue of affordable access to treatment for AIDS, which has gathered international attention in recent months, is hopefully a pointer in the right direction. The TRIPS agreement should not be allowed to hinder the efforts of developing countries to provide affordable access to medicines.

The apex Indian organisations representing various industries are sincerely working towards ensuring a gainful transition with the least disadvantage into the global economy. The government also has to strive to improve infrastructure and provide a facilitating environment for inducing acceleration in trade.

Developed countries have been putting pressure on the inclusion of non-trade issues such as labour standards, environmental protection, human rights, rules on investment, competition policy in the WTO agreements.

Regarding investment/trade facilitation, India has its model investment code which does not allow multinational companies to take the government to international courts before it has sought recourse through the domestic dispute settlement bodies for a period of at least five years. This is because, in the past, the Government of India has been taken to international arbitration courts on multiple occasions.

India has objected to the freeing of e-commerce as it feels that the country's digital penetration is not yet adequate. India also feels that Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) will not be able to compete with countries with deeper internet penetration who can gain better access to international markets. As far as talks on framing of rules and regulations to govern e-commerce are concerned, India wants the 1998 agenda to be the basis of any conversation about this subject.

This is because by asserting that particular developing countries are not observing and implementing the rules regarding the non-trade issues so that the developed countries can ban the imports of some goods in their countries, as the USA has been trying to do so from time to time. India is against any inclusion of non-trade issues that are directed in the long run at enforcing protectionist measures, particularly against developing countries.

India has objected to the WTO Secretariat's participation in the recent report 'Reinvigorating Trade and Inclusive Growth' brought out by the World Bank and IMF casting doubts on the efficacy of trade talks involving all nations. The report's suggestion of having plurilateral instead of multilateral trade talks have not found favour with countries such as India. India has contended that institutional reforms of the WTO are best left to the members rather than the WTO Secretariat.

India has further highlighted the increasing trade frictions and the dwindled size of the Appellate tribunal, which among other things, is affecting dispute resolution. India has maintained that it is committed to working along with other countries to reform the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to ensure that it continues to be an engine for global trade. India also believes that while an institution like the WTO is required and should remain intact, it needs to change.

India recently drew up a proposal aimed at reforming the dispute settlement mechanism, rule-making and transparency requirements. India's move assumes significance in the backdrop of growing protectionism. The proposals were to be floated at the informal ministerial gathering at the recently held World Economic Forum meeting in Davos in January 2019. India's reform paper comes in the wake of the continuing US blockage of the appointment of judges at the WTO for more than two years. India has been asking for a resolution of the appellate body issue because it feels that this is central to the very essence of WTO and unless addressed, the WTO might well turn into a discussion body.

At the WTO meeting, India spelt out its position on some of the new ideas that have been proposed in the Geneva WTO round as a possible way forward. Ruling out any freezing of the custom duties at the current levels (Tariff standstill) India pointed out that this amounted to the developing countries ceding their policy space and being denied any recognition for their autonomous liberalization.

Besides unhinging the negotiated formula on tariff reductions it would force the developing countries to take on commitments going much beyond what was envisaged for at the end of the Doha Round. Similarly, on the issue of export restrictions on agricultural products, any dilution of the flexibilities available under the WTO regime for imposing export restrictions and taxes was unacceptable. It was imperative that the WTO while taking up all manner of the new challenges does not forget the traditional challenge of development.

India called for continued solidarity and reinvigorated engagement so that the current impasse in the Doha negotiations is broken and the attempts to replace the development centric agenda are thwarted. It cautioned against the possibility of losing the progress and the balance achieved so painstakingly over the last decade, particularly on the reforms of the agricultural trading system. The global community should not allow this opportunity to slip away or allow a dilution of the Doha mandate.

It is the responsibility of both Developing and Developed countries to evolve a common position on the way forward on the Doha Development Agenda. India views WTO as an institution that ensures a level playing field in global trade flows and creates a paradigm of equitable and inclusive growth. India is emphatic that urgent steps should be taken to usher in much-delayed changes in the current agricultural trading regime which negatively impact the livelihood concerns of billions of subsistence farmers in the developing world.

The WTO ministers coordinated their positions on the important aspects of agricultural trade, including the large trade-distorting subsidies doled out by the developed countries, and agreed on preserving the centrality of development as the core agenda. While unequivocally expressing its desire to bring this Round to a balanced conclusion, India underlined the need to keep the negotiating process transparent and inclusive.

The importance of strengthening the WTO especially in light of the new forms of protectionism that adversely affected developing countries was done by India. It urged members to get a multilateral trade deal done, not only for trade liberalization and rule building but also for the credibility of the multilateral trading system. Plurilateral trading arrangements, among a few, cannot substitute the multilateral system and are also against the spirit of the fundamental WTO principles of transparency and inclusiveness.

India was open to considering new issues within the mandates of the regular WTO organs as long as these are discussed inclusively and transparently. India said the countries, which were once harbingers of free trade, had themselves started looking inwards. "Protectionist measures must be resisted by all WTO members and the multilateral institutions must be strengthened. In the challenging backdrop of global economic downturn, all countries must eschew protectionism which can only be counter-productive as it will deepen the recession and delay recovery." The need of the hour was enhanced economic engagement and free flow of trade. The global community must maintain the spirit of multilateralism and the WTO has stood as a bulwark against a rising tide of protectionism.

India focused on saving lives and livelihoods by its willingness to take short-term pain for long-term gain, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, an early intense lockdown provided a win-win strategy to save lives and preserve livelihoods via economic recovery in the medium to longterm (Economic Division Affairs, Ministry of Finance, India). On the other hand, strong V-shaped recovery of economic activity was further confirmed by Index of Industrial Production (IIP) data which showed that the recovery in the IIP resulted in a growth of -1.9% in Nov 2020 as compared to a growth of 2.1% in Nov 2019.

India focused on saving lives and livelihoods by its willingness to take short-term pain for long-term gain, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, an early intense lockdown provided a win-win strategy to save lives and preserve livelihoods via economic recovery in the medium to long-term10. On the other hand, strong V-shaped recovery of economic activity was further confirmed by Index of Industrial Production (IIP) data which showed that the recovery in the IIP resulted in a growth of -1.9% in Nov 2020 as compared to a growth of 2.1% in Nov 2019.

Meanwhile, Further improvement and firming up in industrial activities are foreseen with the Government enhancing capital expenditure, the vaccination drive, and the resolute push forward on long-pending reform measures, besides that, the Food Processing Industries (FPI) sector growing at an Average Annual Growth Rate (AAGR) of around 9.99% as compared to around 3.12% in Agriculture and 8.25% in Manufacturing at 2011-12 prices in the last 5 years ending 2018-19. Furthermore, consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation stood at 4.6% in December 2020, mainly driven by the rise in food inflation (from 6.7% in 2019-20 to 9.1% in April-December 2020, owing to build up in vegetable prices).

Figure 4.1: Annual Growth, Comparison of GDP, Inflation, and Industrial Production

Source: Bloomberg/MPD Staff Calculation

Meanwhile, the fiscal deficit of the Central Government for 2019-20 is placed at 3.8% of GDP in the revised estimates as against 3.3% of GDP in the budget estimates. The fiscal deficit is budgeted to decline to 3.5% of GDP in 2020-21. Besides, according to the Government, the deviation in 2019-20 from the fiscal deficit target was necessitated on account of structural reforms such as reductions in corporation tax, furthermore, the fiscal expansion is within the provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003. A similar variation from the 2020-21 target of 3% of GDP is anticipated on account of the spillover impact of the reforms. It is expected that government will return to the path of fiscal consolidation in the medium term (3.3% in 2021-22 and 3.1% in 2022-23) (News Letter, SAARC Finance).

Monetary Policy of India

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered the setting and conduct of monetary policy across the world. The global economy had plunged into its deepest contraction in living memory in Q2:2020, with over 3.5 crore infections, including 10.4 lakh confirmed deaths as of October 7, 2020, with massive supply disruptions and demand destruction from employment and income losses on a scale not seen before, the unconventional has become conventional in the ethos of monetary policy making. Central banks have gone where they have feared to tread before: below the so-called zero lower bound on interest rates; to the outer limits of quantitative and credit easing and beyond. They have undertaken what even until recently they considered as the commission of original sins - the monetisation of fiscal deficits and the management of yield curves.

Central bank communication has also turned a radical corner. Ultra-accommodative stances and more policy actions to fight the pandemic have been assured into the foreseeable future, even at the cost of volatility in financial markets shaken by this resolve, and untoward currency movements. This unprecedented monetary policy activism appears to have put equally unprecedented fiscal stimuli in the shade.

In India, with the second-highest caseload in the world - over 67 lakh infections including 1 lakh deaths as of October 7, 2020, the highest daily infections, the severest lockdown in the world during April-May, and re-clamping of containment measures and localized lockdowns thereafter as infections surged into the interior, real GDP fell by a record 23.9 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) in Q1:2020-21 (April-June 2020). Private consumption and investment slumped precipitously, only partly cushioned by government spending.

On the supply side, industry, as well as services sectors, recorded deep contractions, and only agriculture exhibited resilience. Meanwhile, supply bottlenecks exacerbated by social distancing and higher taxes pushed up inflation sharply, with pressures evident in the prices of both food and non-food items. At 6.7 per cent in August, consumer price index (CPI) inflation was ruling above the upper tolerance band of the inflation target, posing testing challenges for the conduct of monetary policy, going forward.

Real GDP declined by an unprecedented 23.9 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and domestic economic activity remains badly hit by the unrelenting pandemic. High-frequency indicators, which were looking up in June with the phased unlocking of the economy, levelled off in July amidst the re-imposition of local lockdowns due to a surge in fresh cases.

In August, some indicators started improving again and strengthened in September. The agricultural sector remains a bright spot, supported by a normal monsoon, robust Kharif sowing and adequate reservoir levels. The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Rojgar Yojana and increased wages under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is also supporting rural demand. On the other hand, urban demand remains weak. Indicators relating to industry and services present a mixed picture.

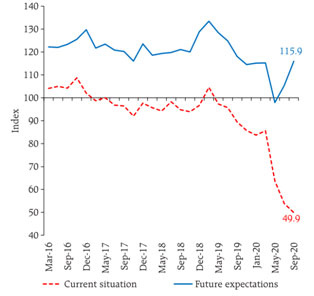

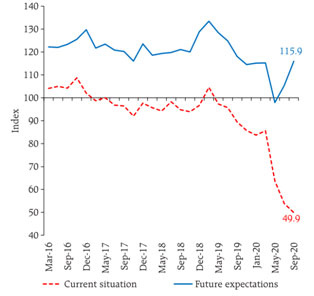

Turning to the forward-looking surveys, consumer confidence for the year ahead improved in the September 2020 round, driven by improved sentiments on the general economic situation, the employment scenario and income.

Figure 4.2: Consumer Confidence

Source: Consumer Confidence Survey, RBI.

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

At the time of the Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of April 2020, headline inflation, which was ruling above the upper tolerance level of the inflation target, was projected to decline, with rabi crop arrivals inducing a softening of food inflation. COVID-19 has drastically altered that prognosis. The pandemic and the response in the form of social distancing and the severest lockdown in the world caused a virtual seizure of transactions in non-essential items and threw into complete disarray the price collection system.

The National Statistical Office (NSO) suspended the publication of the headline consumer price index (CPI) for April and May. It was not until July 13, 2020, with the lifting of some pandemic-related restrictions and the partial restoration of non-essential activities that the provisional index for June 2020 could be compiled.

Even so, prices could be collected from1030 urban markets and 998 villages that accounted for only 88 per cent of the total sample. As such, the data collected did not meet the adequacy criteria for generating robust estimates of CPI at the state level. Headline indices for April and May were imputed for business continuity purposes.

In its resolution of August 6, 2020, the monetary policy committee (MPC) expressed the view that for monetary policy formulation and conduct, the imputed prints for April and May can be regarded as a break in the CPI series. In terms of acceptable standards of data collection, it is appropriate to compare the headline inflation reading for July 2020 with that of March 2020. The surge in inflation by 90 basis points between these reference dates was diffused across the board, partly offset by a significant moderation in fuel inflation.

Figure 4.3: CPI Inflation (y-o-y)

Sources: National Statistical Office (NSO); and RBI staff estimates.

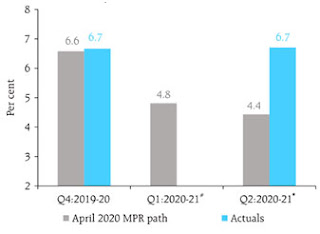

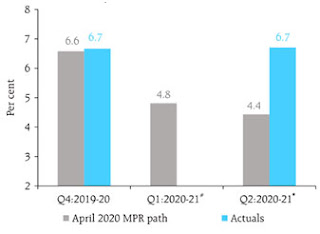

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 (amended in 2016) enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and explain the underlying reasons thereof. The April 2020 MPR had projected moderation in CPI inflation during H1:2020-21 from 6.6 per cent in Q4:2019-20 to 4.8 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and 4.4 per cent in Q2:2020-21, with the caveat that the uncertainty about the depth, spread and duration of COVID-19 could produce drastic changes in these forecasts. With data for Q1 being regarded as a break in the CPI series as cited above, actual inflation outcomes overshot projections by 2.3 percentage points in Q2, largely reflecting the destructive impact of COVID-19.

Figure 4.4: CPI Inflation (y-o-y): Projection versus Actual

#: The NSO did not publish inflation rates for April and May 2020.

*: Projections for entire Q2:2020-21 vis-a-vis actual average inflation during July-August 2020.

Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates.

Demand and Output

Aggregate Demand

The August 2020 data release of the National Statistical Office (NSO) revealed that aggregate demand measured in terms of year-on-year changes in the real gross domestic product (GDP) underwent a contraction of 23.9 per cent in Q1:2020-21, taking GDP to its lowest in the history of the quarterly series.

In Q2, aggregate demand recorded a sequential improvement on the back of robust rural demand and some uptick in urban consumption. Indicators of rural demand, viz., tractor sales, fertilizers production and non-durable consumer goods, have exhibited resilience. Amongst indicators of urban demand, passenger vehicles sales emerged out of contraction in August. The contraction in the production of consumer durables is still high. In Q2, investment remained subdued, as reflected in coincident indicators - steel consumption; cement production; and production and imports of capital goods. The record issuance of corporate bonds in H1:2020, however, suggests financing conditions remain congenial for enabling traction in investment appetite.

Figure 4.5: GDP Growth, its Constituents and Momentum

Note SAAR - Seasonally adjusted annualised rate.

Sources: NSO, Government of India; and RBI staff estimates.

Government Market Borrowings

Table 4.1: Government Market Borrowings

Sources: Government of India; and RBI staff estimates.

As of end-September, `7.66 Lakh crore or 63.8 per cent of the revised gross market borrowings of the central government for the full year 2020-21 has been completed. The central government's market borrowing calendar for H2 has planned gross issuances of `4.34 Lakh crore, sticking to the revised estimate of `12 Lakh crore for the full fiscalyear. States completed gross market borrowings of `3,53,596 crore during the year (up to September 30), comprising 115.8 per cent of the calendar for H1:2020-21.

External Demand

Despite the deterioration of external demand, net exports contributed positively to aggregate demand in Q1:2020-21, as imports contracted faster than exports.

India's exports marked a turnaround and entered positive territory in September after six months of contraction, while imports declined for the seventh consecutive month. In Q2, India's exports were US$ 73.7 billion and imports were US$ 88.3 billion. Despite limited participation, India's merchandise exports were impacted by the massive disruption in global value chains (GVCs) inflicted Q2, India's exports were US$ 73.7 billion and imports were US$ 88.3 billion. Despite limited participation, India's merchandise exports were impacted by the massive disruption in global value chains (GVCs) inflictedby COVID-19.

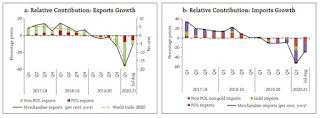

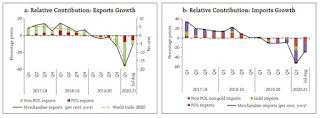

Figure 4.6: Growth in Merchandise and Services Trade

Sources: DGCI&S and RBI

Disaggregated data available for July-August 2020 suggests that among non-oil exports, the decline was pronounced in respect of gems and jewellery, engineering goods, readymade garments and electronic goods. On the other hand, exports of drugs and pharmaceuticals, iron ore and rice recorded robust growth due to increased demand even during the pandemic, underlying their innate resilience.

The decline in imports was broad-based. During July-August, 25 out of 31 major commodity groups, which accounted for 81 per cent of the import basket, witnessed contraction. A steep reduction in crude oil prices and lower domestic demand for petroleum products led to a decline in POL imports, while gold imports plunged with a slump in domestic demand and high gold prices, although a revival of investment demand for gold rekindled. A steep reduction in crude oil prices and lower domestic demand for petroleum products led to a decline in POL imports, while gold imports plunged with a slump in domestic demand and high gold prices, although a revival of investment demand for gold rekindled.

Figure 4.7: Relative Contribution to Exports and Import Growth

Sources: DGCI&S and CPB, Netherlands.

The merchandise trade deficit had narrowed substantially to US$ 9.0 billion in Q1:2020-21 from US$ 49.2 billion a year ago with the first trade surplus of US$ 0.8 billion after a gap of over eighteen years in June 2020. The trade balance, however, turned into a deficit in Q2 (US$ 14.5 billion). The current account balance, which had recorded a marginal surplus of US$ 0.6 billion (0.1 per cent of GDP) in Q4:2019-20 after a gap of twelve years, posted a record surplus of US$ 19.8 billion (3.9 per cent of GDP) in Q1:2020-21.

Financial Markets and Liquidity Conditions

In Q2:2020-21, global financial markets have stabilised after recovering from the tailspin during February and March 2020. In more recent weeks, sentiments have been intermittently dampened by rising infections and geo-political tensions or lifted by news on the progress on the vaccine. In large measure, the calm in financial markets after the turbulence in March has been engendered by liquidity infusions, monetary policy actions by central banks and stimulus measures undertaken by national governments.

Equity markets in major advanced economies (AEs) and emerging market economies (EMEs) have registered handsome gains with the return of risk-on sentiments. Gold prices surged to record highs in early August, but have been range-bound more recently. Bond yields softened and spreads narrowed in the wake of substantial unconventional liquidity operations and strong demand for safe assets; relative to other segments, however, bond markets have moved sideways and in a narrow range.

In currency markets, the US dollar depreciated markedly as fatalities increased amid rising infection numbers and with signals from the US Federal Reserve (FED) that monetary policy would continue to remain accommodative for a long period, reinforced by an average inflation targeting framework allowing transitory target overshoot to support maximum employment.

Domestic Financial Markets

During H1:2020-21, domestic financial markets returned to normalcy with a recovery in trading volumes, narrowing of spreads and rebounds at financial asset prices after a near collapse in market activity, post the imposition of the nation-wide lockdown to combat COVID-19. A slew of monetary, liquidity, credit easing and regulatory measures by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government's stimulus package enthused market sentiment. Nevertheless, concerns about the duration of the pandemic, the large expansion in market borrowings by the public sector, border tensions and rising inflation prints intermittently kept markets on edge.

During H1:2020-21, domestic financial markets returned to normalcy with a recovery in trading volumes, narrowing of spreads and rebounds at financial asset prices after a near collapse in market activity, post the imposition of the nation-wide lockdown to combat COVID-19. A slew of monetary, liquidity, credit easing and regulatory measures by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government's stimulus package enthused market sentiment. Nevertheless, concerns about the duration of the pandemic, the large expansion in market borrowings by the public sector, border tensions and rising inflation prints intermittently kept markets on edge.

Money Market

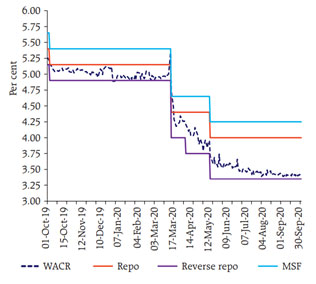

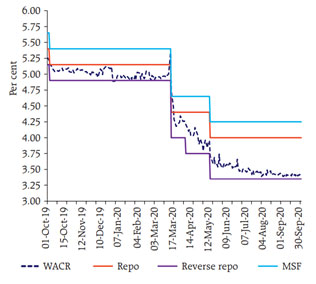

Money markets have remained broadly stable during H1:2020-21 due to proactive liquidity management by the Reserve Bank. In the overnight uncollateralized segment, the weighted average call rate (WACR) - the operating target of monetary policy - remained within the policy corridor although it traded with a distinct downward bias, reflecting the comfortable liquidity and financing conditions.

Figure 4.8: Policy Corridor and WACR

Source: Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Interest rates in the secured overnight segments traded below the reverse repo rate in H1 reflecting the surplus system liquidity conditions and increased lending by mutual funds. As a result, the spread between the collateralised rates and the uncollateralised rate (WACR) widened: the triparty repo rate and the market repo rate traded below the WACR by 59 basis points (bps) and 58 bps, respectively, in H1:2020-21 as against 36 bps and 37 bps, respectively, in H2:2019-20.

Figure 4.9: Money Market Rates

Sources: RBI; CCIL: F-TRAC; CCIL: FBIL; and RBI staff estimates.

Equity Market

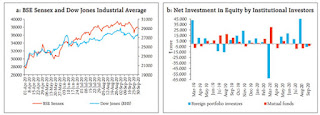

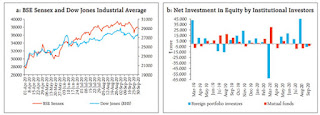

After undergoing intense volatility in Q4:2019-20 following the COVID-19 outbreak with massive disruption in business activity, the Indian equity market made a strong V-shaped recovery in H1:2020- 21. The BSE Sensex gained 46.5 per cent in H1:2020-21 after hitting a low of 25981 on March 23, 2020 (Chart IV.15a). Strong rallies in global equity markets on the back of massive fiscal and monetary stimuli in major countries and the measures are undertaken in India boosted domestic market sentiments.

The recovery continued in July and August on the back of positive news from encouraging trials of the coronavirus vaccine and hopes of more supportive measures by national authorities globally. On the domestic front, the rally in equities was also supported by improvement in the manufacturing PMI for June 2020, reports of disengagement between India and China over border issues and better than expected Q1:2020-21 corporate earnings results.

Domestic market sentiment was tempered during August by contraction in manufacturing PMI and higher-than-expected CPI inflation print for July 2020. The stock market plummeted sharply in the last trading session of the month due to fresh escalation in Indo-China border tensions and witnessed cautious trading ahead of the implementation of new trading norms on margin requirements by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) from September 1, 2020.

Investor sentiment remained insipid in September 2020 amidst concerns over a steady increase in coronavirus infections and weak global cues. After registering moderate gains due to improvement in domestic manufacturing PMI for August 2020, equity sentiments turned negative with the BSE Sensex witnessing its biggest intra-day fall in more than four months on September 24 as the spike in infections in some European countries triggered fears of a second round of lockdown. Bullish sentiments, however, returned towards the end of the month amid expectations of further stimulus measures by the government.

During H1:2020-21, FPIs turned net buyers in the Indian equity market after panic sales in March due to flight to safety. MFs, however, were net sellers to the tune of `24,801 crores during H1:2020-21. Resource mobilisation through public and rights issues of equity increased to `76,830 crores during H1:2020-21 from `60,133 crores in the corresponding period of the previous year.

Figure 4.10: Stock Market Indices and Investment

Sources: Bloomberg; NSDL; and SEBI

Foreign Exchange Market

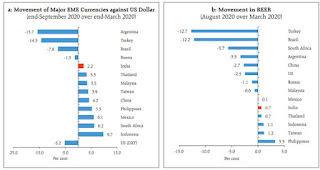

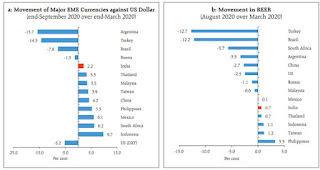

The INR exhibited movements in both directions against the US dollar during H1:2020-21. After depreciating to its lowest level of `76.81 on April 22, 2020, the INR subsequently appreciated owing to FPI flows to the domestic equity market with the return of risk appetite for EME assets and the depreciation of the US dollar. The appreciation of the INR against the US dollar was modest as compared with EME peers.

In terms of the 36-currency nominal effective exchange rate (NEER), the INR depreciated by 0.6 per cent (as at end-September 2020 over the average of March 2020), but it appreciated by 2.1 per cent in terms of the 36-currency real effective exchange rate (REER)during the same period. Between March and August 2020, the appreciation of the INR in terms of the REER was lower than that of the Indonesian rupiah, the Taiwan dollar and the Philippine peso.

Figure 4.11: Cross-Currency Movements

Note: Appreciation (+)/Depreciation (-).

Sources: RBI; FBIL; IMF; Bloomberg; Thomson Reuters; and Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

Credit Market

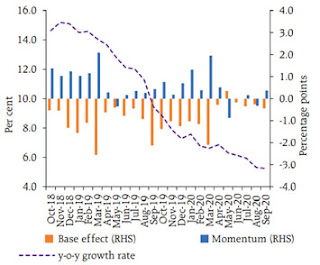

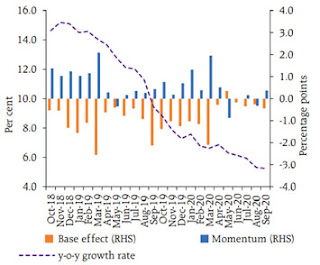

During H1:2020-21, bank credit offtake was anaemic, reflecting weak demand and uncertainty in the wake of the pandemic. Non-food credit growth (y-o-y) at 5.1 per cent as of September 25, 2020, was lower than 8.6 per cent a year ago, driven by weak momentum and base effects.

Figure 4.12: Non-food Credit Growth of SCBs

Note: Monthly numbers are based on the average of the fortnights.

Source: RBI

The slowdown in credit growth was spread across all bank groups, especially foreign banks. Credit growth of the public sector banks remained modest, although with some uptick since March 2020. Of the incremental credit extended by the scheduled commercial banks (SCBs) on a year-on-year basis (September 27, 2019, to September 25, 2020), 62.3 per cent was provided by the public sector banks and 41.2 per cent by the private sector banks, while the share of the foreign banks turned negative.

Figure 4.13: Credit Flow across Bank-Groups

Source: RBI

The deceleration in non-food credit growth was broad-based with credit offtake slowing down in all the major sectors. Though personal loans and credit to agriculture registered some improvement in July 2020,the momentum could not be sustained in August. Credit growth to services and industrial sectors has also tapered off after showing some promise in Q1; 2020-21. Personal loans accounted for the largest share of total credit flow in August 2020, followed by services. While the share of personal loans, services and agriculture increased in August 2020 vis-a-vis the previous year, the share of industry contracted.

Within the industry, credit growth to food processing, mining and quarrying, petroleum, coal products and nuclear fuels, leather and leather products, wood and wood products, and paper and paper products accelerated in August 2020 as compared with a year ago. In contrast, credit growth to chemicals and chemical products, rubber plastic and their products, infrastructure, construction, gems and jewellery, glass and glassware, basic metal and metal products and beverage and tobacco decelerated/contracted.

Figure 4.14: Sectoral Deployment of Credit

Source: RBI

Banks augmented their SLR portfolios in the wake of deceleration in credit offtake and higher government borrowings. Consequently, excess SLR maintained by all scheduled commercial banks increased to 11.1 per cent of net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) in Q2:2020-21 (up to August 28) from 7.1 per cent a year ago.

Figure 4.15: Excess SLR of Banks

Note: Excess SLR is based on the average of all reporting Fridays in the quarter. Data for Q2:2020-21 is up to August 28, 2020.

Source: RBI.

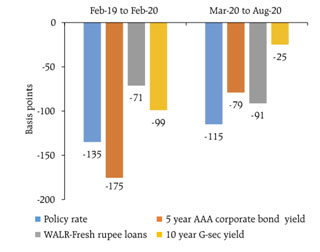

Monetary Policy Transmission

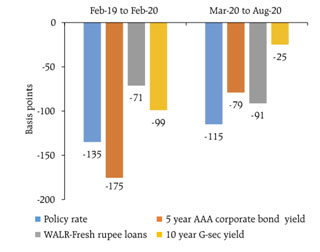

The transmission of policy repo rate changes to deposit and lending rates of banks improved since the April 2020 MPR. The weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans declined by 91 bps since March 2020 in response to the reduction of 115 bps in the policy repo rate and comfortable liquidity conditions.

Figure 4.16: Monetary Transmission - Banks and Markets

Sources: Bloomberg and RBI.

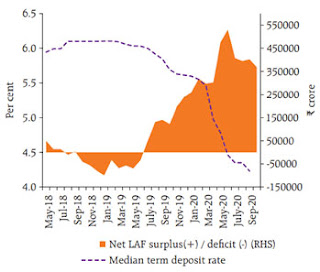

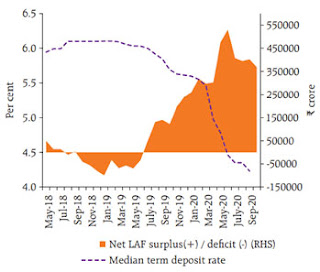

Figure 4.17: Median Term Deposit Rate and Liquidity Conditions

Source: RBI

The pass-through to WALR on fresh rupee loans was higher than the softening of yield on 5-year corporate bonds (79 bps) and yield on 10-year G-Secs during March-August 2020. The WALR on outstanding rupee loans declined by 46 bps during this period, but this transmission is an improvement over the earlier period.

Of the 105 bps reduction in the weighted average domestic term deposit rate (WADTDR) on outstanding rupee deposits during the ongoing easing cycle (i.e., since February 2019), a little over half of the decline, i.e. 59 bps occurred since March 2020. The median term deposit rate, which reflects the prevailing card rates, has registered a sizable decline of 125 bps since March 2020, reflecting the combined impact of surplus liquidity, the introduction of external benchmark-based pricing of loans and weak credit demand conditions.

Conclusion:

Domestic financial markets have gradually regained normalcy in the wake of sizable conventional and unconventional measures by the Reserve Bank. Turnover in various market segments is increasing and spreads have narrowed appreciably. The return of capital inflows is an indicator of growing investor confidence in the Indian economy.

The pace of monetary transmission has also quickened, but credit growth remains feeble, clouding the outlook. Going forward, liquidity conditions would continue to be calibrated, consistent with the stance of monetary policy while ensuring normalcy in the functioning of financial markets and institutions and conducive financial conditions. Efficient monetary policy transmission, particularly to the credit market, would continue to assume priority in the hierarchy of policy objectives.

Written By: Sayed Qudrathashimy, Student of LLM (International Law), Department of Studies in Law, University of Mysore

e-mail: sayedqudrathashimy@law.uni-mysore.ac.in

Various trade disputes of India with other nations have been settled through WTO. India has also played an important part in the effective formulation of major trade policies. By being a member of WTO, several countries are now trading with India, thus giving a boost to production, employment, the standard of living and an opportunity to maximize the use of the world resources.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) as an institution has perhaps never come under as much of a siege as now. Increasing protectionism, inadequate judges in the Appellate Tribunal for dispute resolution, increasing number of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) etc. have resulted in member countries questioning the efficacy of WTO as an institution meant to ensure free trade and promote multilateralism. Apart from the ongoing trade war-like situation between USA and China, there have been trading skirmishes across the globe.

India (along with a few other developing countries) has and continues to have objections (raised and ventilated through WTO Forums) on issues like agriculture especially subsidies in the context of food security etc. and trade facilitation.

India has consistently taken the stand that the launch of any new round of talks depends on a full convergence of views amongst the entire WTO membership on the scope and framework for such negotiations. India's more urgent task is to resolve the concerns of developing countries on the implementation of the Uruguay Round agreements. India is against calls for new commitments from the developing world for achieving symmetry and equity in the existing agreements. It is in favour of non-trade issues being permanently kept off the negotiating table.

Ensuring food and livelihood security is critical, particularly for a largely agrarian economy like India. India's proposal in ongoing negotiations includes suggestions like allowing developing countries to maintain an appropriate level of tariff bindings, commensurate with their developmental needs and the prevailing distortions in international markets.

India is also seeking a separate safeguard mechanism including provision for imposition of quantitative restrictions under specified circumstances, particularly in case of a surge in imports or decline in prices; exemptions for developing countries from obligations to provide minimum market access; exemptions of all measures taken by developing countries for poverty alleviation, rural development and rural employment.

India's immediate priority is that the agreements reached earlier with the developing countries should be implemented to correct inherent imbalances in some of the Uruguay Round agreements. Sincere and meaningful implementation of commitments undertaken by developed countries and operationalization of all special and differential treatment clauses for developing countries in the various agreements is made.

India also strongly favourthe extension of higher levels of protection to the geographical indications for products like Basmati rice, Darjeeling tea, and Alphonso mangoes at par with that provided to wines and spirits under the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. In the TRIMS (Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures) review India wants flexibility for developing countries in adopting appropriate domestic policy while permitting foreign investment.

Developed countries are pushing for a comprehensive agenda like rules on investment, environment, competition policy, trade facilitation, transparency in government procurement, labour standards etc. They are pressing for incorporating non-trade issues of environment and labour standards.

Using as an excuse that the production of products in developing countries are not being done under proper environmental and labour standards, they can ban the imports of their products or impose other non-tariff restrictions. The developing countries are opposed to these non-trade issues.

Some critics of WTO have expressed their fears that Indian farmers are threatened by the WTO. There is however no adverse impact. India has bound its tariff to the extent of 100 per cent for primary agricultural products, 150 per cent for processed agricultural products and 300 per cent for edible oils. A few agricultural products had been bound historically at low levels but these bindings have been raised following the Article XXVIII negotiations held in this regard.

It has also been possible to maintain without hindrance the domestic policy instruments for the promotion of agriculture or targeted supply of food grains. Domestic policy measures like the operation of minimum support price, public distribution system as well as provision of input subsidies to agriculture have not in any way been constrained by the WTO agreement.

Certain provisions in the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) also give us the flexibility to provide support for research, pest and disease control, marketing and promotion services, infrastructure development, payments for relief from natural disasters, payments under the regional assistance programmes for disadvantaged regions and payments under environmental programmes. Indian farmers now need to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the AoA, by addressing productivity issues and making their products more competitive globally.

India (along with a few other developing countries) has and continues to have objections (raised and ventilated through WTO Forums) on issues like agriculture especially subsidies in the context of food security etc. and trade facilitation.

India has been pushing agricultural issues at the WTO. Public stock holding (which includes purchasing, stockpiling and distributing food by Governments in times of necessity) is very important for India's food security. While stockpiling and distributing are as per WTO guidelines, the purchasing of food by governments at a price higher than the market price is considered by the WTO as a trade-distorting subsidy.

The 11th Ministerial Conference held in Buenos Aires in 2017 did not result in any permanent solution to the issue of public stock holding. India has been a votary of a permanent solution to the issue of stock holding. The sticking point in this issue, as far as India is concerned, has been how the Minimum Support Price (MSP) (MSP is the guaranteed price fixed by the Government of India and paid to the farmers for their produce. It is essentially a support mechanism extended by the Government to the farmers to ensure that the farmers get a minimum profit for their products especially when prices in the open market are less than the costs incurred) is fixed.

According to the WTO's Agreement on Agriculture, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) would have to be calculated based onthe price of food grains in 1986-88 and the total subsidy would have to be below 10 per cent of the total value of production. India has strongly disputed this formula because the current prices are much higher and hence the total MSP given as subsidy would also be higher. Countries like India and China have opposed the huge production-related price distorting subsidies given by the developed countries like the US and the EU to their farmers. The US alone gives around USD 150 billion in direct subsidies to farmers.

Indian industry has had to face greater competition in the wake of globalisation. But it has completed, as can be inferred from the fact that there has been no particular surge in imports. In fact, as per the provisional data for 2000-01, non-oil imports declined by 14 per cent whileexports rose by over 20 per cent in the same period. A close watch is also being kept to ensure that Indian industry does not have to face unfair competition from dumped or subsidised imports of other countries.

As for drug prices, safeguards are provided like compulsory licensing, price controls, and parallel imports which should help address this concern. It must also be recognised that the prices of medicines are influenced by several factors including the level of competition, size of the market, purchasing capacity etc.

The issue of affordable access to treatment for AIDS, which has gathered international attention in recent months, is hopefully a pointer in the right direction. The TRIPS agreement should not be allowed to hinder the efforts of developing countries to provide affordable access to medicines.

The apex Indian organisations representing various industries are sincerely working towards ensuring a gainful transition with the least disadvantage into the global economy. The government also has to strive to improve infrastructure and provide a facilitating environment for inducing acceleration in trade.

Developed countries have been putting pressure on the inclusion of non-trade issues such as labour standards, environmental protection, human rights, rules on investment, competition policy in the WTO agreements.

Regarding investment/trade facilitation, India has its model investment code which does not allow multinational companies to take the government to international courts before it has sought recourse through the domestic dispute settlement bodies for a period of at least five years. This is because, in the past, the Government of India has been taken to international arbitration courts on multiple occasions.

India has objected to the freeing of e-commerce as it feels that the country's digital penetration is not yet adequate. India also feels that Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) will not be able to compete with countries with deeper internet penetration who can gain better access to international markets. As far as talks on framing of rules and regulations to govern e-commerce are concerned, India wants the 1998 agenda to be the basis of any conversation about this subject.

This is because by asserting that particular developing countries are not observing and implementing the rules regarding the non-trade issues so that the developed countries can ban the imports of some goods in their countries, as the USA has been trying to do so from time to time. India is against any inclusion of non-trade issues that are directed in the long run at enforcing protectionist measures, particularly against developing countries.

India has objected to the WTO Secretariat's participation in the recent report 'Reinvigorating Trade and Inclusive Growth' brought out by the World Bank and IMF casting doubts on the efficacy of trade talks involving all nations. The report's suggestion of having plurilateral instead of multilateral trade talks have not found favour with countries such as India. India has contended that institutional reforms of the WTO are best left to the members rather than the WTO Secretariat.

India has further highlighted the increasing trade frictions and the dwindled size of the Appellate tribunal, which among other things, is affecting dispute resolution. India has maintained that it is committed to working along with other countries to reform the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to ensure that it continues to be an engine for global trade. India also believes that while an institution like the WTO is required and should remain intact, it needs to change.

India recently drew up a proposal aimed at reforming the dispute settlement mechanism, rule-making and transparency requirements. India's move assumes significance in the backdrop of growing protectionism. The proposals were to be floated at the informal ministerial gathering at the recently held World Economic Forum meeting in Davos in January 2019. India's reform paper comes in the wake of the continuing US blockage of the appointment of judges at the WTO for more than two years. India has been asking for a resolution of the appellate body issue because it feels that this is central to the very essence of WTO and unless addressed, the WTO might well turn into a discussion body.

At the WTO meeting, India spelt out its position on some of the new ideas that have been proposed in the Geneva WTO round as a possible way forward. Ruling out any freezing of the custom duties at the current levels (Tariff standstill) India pointed out that this amounted to the developing countries ceding their policy space and being denied any recognition for their autonomous liberalization.

Besides unhinging the negotiated formula on tariff reductions it would force the developing countries to take on commitments going much beyond what was envisaged for at the end of the Doha Round. Similarly, on the issue of export restrictions on agricultural products, any dilution of the flexibilities available under the WTO regime for imposing export restrictions and taxes was unacceptable. It was imperative that the WTO while taking up all manner of the new challenges does not forget the traditional challenge of development.

India called for continued solidarity and reinvigorated engagement so that the current impasse in the Doha negotiations is broken and the attempts to replace the development centric agenda are thwarted. It cautioned against the possibility of losing the progress and the balance achieved so painstakingly over the last decade, particularly on the reforms of the agricultural trading system. The global community should not allow this opportunity to slip away or allow a dilution of the Doha mandate.

It is the responsibility of both Developing and Developed countries to evolve a common position on the way forward on the Doha Development Agenda. India views WTO as an institution that ensures a level playing field in global trade flows and creates a paradigm of equitable and inclusive growth. India is emphatic that urgent steps should be taken to usher in much-delayed changes in the current agricultural trading regime which negatively impact the livelihood concerns of billions of subsistence farmers in the developing world.

The WTO ministers coordinated their positions on the important aspects of agricultural trade, including the large trade-distorting subsidies doled out by the developed countries, and agreed on preserving the centrality of development as the core agenda. While unequivocally expressing its desire to bring this Round to a balanced conclusion, India underlined the need to keep the negotiating process transparent and inclusive.

The importance of strengthening the WTO especially in light of the new forms of protectionism that adversely affected developing countries was done by India. It urged members to get a multilateral trade deal done, not only for trade liberalization and rule building but also for the credibility of the multilateral trading system. Plurilateral trading arrangements, among a few, cannot substitute the multilateral system and are also against the spirit of the fundamental WTO principles of transparency and inclusiveness.

India was open to considering new issues within the mandates of the regular WTO organs as long as these are discussed inclusively and transparently. India said the countries, which were once harbingers of free trade, had themselves started looking inwards. "Protectionist measures must be resisted by all WTO members and the multilateral institutions must be strengthened. In the challenging backdrop of global economic downturn, all countries must eschew protectionism which can only be counter-productive as it will deepen the recession and delay recovery." The need of the hour was enhanced economic engagement and free flow of trade. The global community must maintain the spirit of multilateralism and the WTO has stood as a bulwark against a rising tide of protectionism.

India focused on saving lives and livelihoods by its willingness to take short-term pain for long-term gain, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, an early intense lockdown provided a win-win strategy to save lives and preserve livelihoods via economic recovery in the medium to longterm (Economic Division Affairs, Ministry of Finance, India). On the other hand, strong V-shaped recovery of economic activity was further confirmed by Index of Industrial Production (IIP) data which showed that the recovery in the IIP resulted in a growth of -1.9% in Nov 2020 as compared to a growth of 2.1% in Nov 2019.

India focused on saving lives and livelihoods by its willingness to take short-term pain for long-term gain, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, an early intense lockdown provided a win-win strategy to save lives and preserve livelihoods via economic recovery in the medium to long-term10. On the other hand, strong V-shaped recovery of economic activity was further confirmed by Index of Industrial Production (IIP) data which showed that the recovery in the IIP resulted in a growth of -1.9% in Nov 2020 as compared to a growth of 2.1% in Nov 2019.

Meanwhile, Further improvement and firming up in industrial activities are foreseen with the Government enhancing capital expenditure, the vaccination drive, and the resolute push forward on long-pending reform measures, besides that, the Food Processing Industries (FPI) sector growing at an Average Annual Growth Rate (AAGR) of around 9.99% as compared to around 3.12% in Agriculture and 8.25% in Manufacturing at 2011-12 prices in the last 5 years ending 2018-19. Furthermore, consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation stood at 4.6% in December 2020, mainly driven by the rise in food inflation (from 6.7% in 2019-20 to 9.1% in April-December 2020, owing to build up in vegetable prices).

Figure 4.1: Annual Growth, Comparison of GDP, Inflation, and Industrial Production

Source: Bloomberg/MPD Staff Calculation

Meanwhile, the fiscal deficit of the Central Government for 2019-20 is placed at 3.8% of GDP in the revised estimates as against 3.3% of GDP in the budget estimates. The fiscal deficit is budgeted to decline to 3.5% of GDP in 2020-21. Besides, according to the Government, the deviation in 2019-20 from the fiscal deficit target was necessitated on account of structural reforms such as reductions in corporation tax, furthermore, the fiscal expansion is within the provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003. A similar variation from the 2020-21 target of 3% of GDP is anticipated on account of the spillover impact of the reforms. It is expected that government will return to the path of fiscal consolidation in the medium term (3.3% in 2021-22 and 3.1% in 2022-23) (News Letter, SAARC Finance).

Monetary Policy of India

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally altered the setting and conduct of monetary policy across the world. The global economy had plunged into its deepest contraction in living memory in Q2:2020, with over 3.5 crore infections, including 10.4 lakh confirmed deaths as of October 7, 2020, with massive supply disruptions and demand destruction from employment and income losses on a scale not seen before, the unconventional has become conventional in the ethos of monetary policy making. Central banks have gone where they have feared to tread before: below the so-called zero lower bound on interest rates; to the outer limits of quantitative and credit easing and beyond. They have undertaken what even until recently they considered as the commission of original sins - the monetisation of fiscal deficits and the management of yield curves.

Central bank communication has also turned a radical corner. Ultra-accommodative stances and more policy actions to fight the pandemic have been assured into the foreseeable future, even at the cost of volatility in financial markets shaken by this resolve, and untoward currency movements. This unprecedented monetary policy activism appears to have put equally unprecedented fiscal stimuli in the shade.

In India, with the second-highest caseload in the world - over 67 lakh infections including 1 lakh deaths as of October 7, 2020, the highest daily infections, the severest lockdown in the world during April-May, and re-clamping of containment measures and localized lockdowns thereafter as infections surged into the interior, real GDP fell by a record 23.9 per cent year-on-year (y-o-y) in Q1:2020-21 (April-June 2020). Private consumption and investment slumped precipitously, only partly cushioned by government spending.

On the supply side, industry, as well as services sectors, recorded deep contractions, and only agriculture exhibited resilience. Meanwhile, supply bottlenecks exacerbated by social distancing and higher taxes pushed up inflation sharply, with pressures evident in the prices of both food and non-food items. At 6.7 per cent in August, consumer price index (CPI) inflation was ruling above the upper tolerance band of the inflation target, posing testing challenges for the conduct of monetary policy, going forward.

Real GDP declined by an unprecedented 23.9 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and domestic economic activity remains badly hit by the unrelenting pandemic. High-frequency indicators, which were looking up in June with the phased unlocking of the economy, levelled off in July amidst the re-imposition of local lockdowns due to a surge in fresh cases.

In August, some indicators started improving again and strengthened in September. The agricultural sector remains a bright spot, supported by a normal monsoon, robust Kharif sowing and adequate reservoir levels. The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Rojgar Yojana and increased wages under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) is also supporting rural demand. On the other hand, urban demand remains weak. Indicators relating to industry and services present a mixed picture.

Turning to the forward-looking surveys, consumer confidence for the year ahead improved in the September 2020 round, driven by improved sentiments on the general economic situation, the employment scenario and income.

Figure 4.2: Consumer Confidence

Source: Consumer Confidence Survey, RBI.

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

At the time of the Monetary Policy Report (MPR) of April 2020, headline inflation, which was ruling above the upper tolerance level of the inflation target, was projected to decline, with rabi crop arrivals inducing a softening of food inflation. COVID-19 has drastically altered that prognosis. The pandemic and the response in the form of social distancing and the severest lockdown in the world caused a virtual seizure of transactions in non-essential items and threw into complete disarray the price collection system.

The National Statistical Office (NSO) suspended the publication of the headline consumer price index (CPI) for April and May. It was not until July 13, 2020, with the lifting of some pandemic-related restrictions and the partial restoration of non-essential activities that the provisional index for June 2020 could be compiled.

Even so, prices could be collected from1030 urban markets and 998 villages that accounted for only 88 per cent of the total sample. As such, the data collected did not meet the adequacy criteria for generating robust estimates of CPI at the state level. Headline indices for April and May were imputed for business continuity purposes.

In its resolution of August 6, 2020, the monetary policy committee (MPC) expressed the view that for monetary policy formulation and conduct, the imputed prints for April and May can be regarded as a break in the CPI series. In terms of acceptable standards of data collection, it is appropriate to compare the headline inflation reading for July 2020 with that of March 2020. The surge in inflation by 90 basis points between these reference dates was diffused across the board, partly offset by a significant moderation in fuel inflation.

Figure 4.3: CPI Inflation (y-o-y)

Sources: National Statistical Office (NSO); and RBI staff estimates.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 (amended in 2016) enjoins the RBI to set out deviations of actual inflation outcomes from projections, if any, and explain the underlying reasons thereof. The April 2020 MPR had projected moderation in CPI inflation during H1:2020-21 from 6.6 per cent in Q4:2019-20 to 4.8 per cent in Q1:2020-21 and 4.4 per cent in Q2:2020-21, with the caveat that the uncertainty about the depth, spread and duration of COVID-19 could produce drastic changes in these forecasts. With data for Q1 being regarded as a break in the CPI series as cited above, actual inflation outcomes overshot projections by 2.3 percentage points in Q2, largely reflecting the destructive impact of COVID-19.

Figure 4.4: CPI Inflation (y-o-y): Projection versus Actual

#: The NSO did not publish inflation rates for April and May 2020.

*: Projections for entire Q2:2020-21 vis-a-vis actual average inflation during July-August 2020.

Sources: NSO; and RBI staff estimates.

Demand and Output

Aggregate Demand

The August 2020 data release of the National Statistical Office (NSO) revealed that aggregate demand measured in terms of year-on-year changes in the real gross domestic product (GDP) underwent a contraction of 23.9 per cent in Q1:2020-21, taking GDP to its lowest in the history of the quarterly series.

In Q2, aggregate demand recorded a sequential improvement on the back of robust rural demand and some uptick in urban consumption. Indicators of rural demand, viz., tractor sales, fertilizers production and non-durable consumer goods, have exhibited resilience. Amongst indicators of urban demand, passenger vehicles sales emerged out of contraction in August. The contraction in the production of consumer durables is still high. In Q2, investment remained subdued, as reflected in coincident indicators - steel consumption; cement production; and production and imports of capital goods. The record issuance of corporate bonds in H1:2020, however, suggests financing conditions remain congenial for enabling traction in investment appetite.

Figure 4.5: GDP Growth, its Constituents and Momentum

Note SAAR - Seasonally adjusted annualised rate.

Sources: NSO, Government of India; and RBI staff estimates.

Government Market Borrowings

Table 4.1: Government Market Borrowings

| Item | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 (up to Sep 30, 2020) | ||||||

| Centre | States | Total | Centre | States | Total | Centre | States | Total | |

| Net borrowings | 4,22,737 | 3,48,643 | 7,71,380 | 4,73,972 | 4,87,454 | 9,61,426 | 6,35,428 | 2,98,989 | 9,34,417 |

| Gross borrowings | 5,71,000 | 4,78,323 | 10,49,323 | 7,10,000 | 6,34,521 | 13,44,521 | 7,66,000 | 3,53,596 | 11,19,596 |

As of end-September, `7.66 Lakh crore or 63.8 per cent of the revised gross market borrowings of the central government for the full year 2020-21 has been completed. The central government's market borrowing calendar for H2 has planned gross issuances of `4.34 Lakh crore, sticking to the revised estimate of `12 Lakh crore for the full fiscalyear. States completed gross market borrowings of `3,53,596 crore during the year (up to September 30), comprising 115.8 per cent of the calendar for H1:2020-21.

External Demand

Despite the deterioration of external demand, net exports contributed positively to aggregate demand in Q1:2020-21, as imports contracted faster than exports.

India's exports marked a turnaround and entered positive territory in September after six months of contraction, while imports declined for the seventh consecutive month. In Q2, India's exports were US$ 73.7 billion and imports were US$ 88.3 billion. Despite limited participation, India's merchandise exports were impacted by the massive disruption in global value chains (GVCs) inflicted Q2, India's exports were US$ 73.7 billion and imports were US$ 88.3 billion. Despite limited participation, India's merchandise exports were impacted by the massive disruption in global value chains (GVCs) inflictedby COVID-19.

Figure 4.6: Growth in Merchandise and Services Trade

Sources: DGCI&S and RBI

Disaggregated data available for July-August 2020 suggests that among non-oil exports, the decline was pronounced in respect of gems and jewellery, engineering goods, readymade garments and electronic goods. On the other hand, exports of drugs and pharmaceuticals, iron ore and rice recorded robust growth due to increased demand even during the pandemic, underlying their innate resilience.

The decline in imports was broad-based. During July-August, 25 out of 31 major commodity groups, which accounted for 81 per cent of the import basket, witnessed contraction. A steep reduction in crude oil prices and lower domestic demand for petroleum products led to a decline in POL imports, while gold imports plunged with a slump in domestic demand and high gold prices, although a revival of investment demand for gold rekindled. A steep reduction in crude oil prices and lower domestic demand for petroleum products led to a decline in POL imports, while gold imports plunged with a slump in domestic demand and high gold prices, although a revival of investment demand for gold rekindled.

Figure 4.7: Relative Contribution to Exports and Import Growth

Sources: DGCI&S and CPB, Netherlands.

The merchandise trade deficit had narrowed substantially to US$ 9.0 billion in Q1:2020-21 from US$ 49.2 billion a year ago with the first trade surplus of US$ 0.8 billion after a gap of over eighteen years in June 2020. The trade balance, however, turned into a deficit in Q2 (US$ 14.5 billion). The current account balance, which had recorded a marginal surplus of US$ 0.6 billion (0.1 per cent of GDP) in Q4:2019-20 after a gap of twelve years, posted a record surplus of US$ 19.8 billion (3.9 per cent of GDP) in Q1:2020-21.

Financial Markets and Liquidity Conditions

In Q2:2020-21, global financial markets have stabilised after recovering from the tailspin during February and March 2020. In more recent weeks, sentiments have been intermittently dampened by rising infections and geo-political tensions or lifted by news on the progress on the vaccine. In large measure, the calm in financial markets after the turbulence in March has been engendered by liquidity infusions, monetary policy actions by central banks and stimulus measures undertaken by national governments.

Equity markets in major advanced economies (AEs) and emerging market economies (EMEs) have registered handsome gains with the return of risk-on sentiments. Gold prices surged to record highs in early August, but have been range-bound more recently. Bond yields softened and spreads narrowed in the wake of substantial unconventional liquidity operations and strong demand for safe assets; relative to other segments, however, bond markets have moved sideways and in a narrow range.

In currency markets, the US dollar depreciated markedly as fatalities increased amid rising infection numbers and with signals from the US Federal Reserve (FED) that monetary policy would continue to remain accommodative for a long period, reinforced by an average inflation targeting framework allowing transitory target overshoot to support maximum employment.

Domestic Financial Markets

During H1:2020-21, domestic financial markets returned to normalcy with a recovery in trading volumes, narrowing of spreads and rebounds at financial asset prices after a near collapse in market activity, post the imposition of the nation-wide lockdown to combat COVID-19. A slew of monetary, liquidity, credit easing and regulatory measures by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government's stimulus package enthused market sentiment. Nevertheless, concerns about the duration of the pandemic, the large expansion in market borrowings by the public sector, border tensions and rising inflation prints intermittently kept markets on edge.

During H1:2020-21, domestic financial markets returned to normalcy with a recovery in trading volumes, narrowing of spreads and rebounds at financial asset prices after a near collapse in market activity, post the imposition of the nation-wide lockdown to combat COVID-19. A slew of monetary, liquidity, credit easing and regulatory measures by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the government's stimulus package enthused market sentiment. Nevertheless, concerns about the duration of the pandemic, the large expansion in market borrowings by the public sector, border tensions and rising inflation prints intermittently kept markets on edge.

Money Market

Money markets have remained broadly stable during H1:2020-21 due to proactive liquidity management by the Reserve Bank. In the overnight uncollateralized segment, the weighted average call rate (WACR) - the operating target of monetary policy - remained within the policy corridor although it traded with a distinct downward bias, reflecting the comfortable liquidity and financing conditions.

Figure 4.8: Policy Corridor and WACR

Source: Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

Interest rates in the secured overnight segments traded below the reverse repo rate in H1 reflecting the surplus system liquidity conditions and increased lending by mutual funds. As a result, the spread between the collateralised rates and the uncollateralised rate (WACR) widened: the triparty repo rate and the market repo rate traded below the WACR by 59 basis points (bps) and 58 bps, respectively, in H1:2020-21 as against 36 bps and 37 bps, respectively, in H2:2019-20.

Figure 4.9: Money Market Rates

Sources: RBI; CCIL: F-TRAC; CCIL: FBIL; and RBI staff estimates.

Equity Market

After undergoing intense volatility in Q4:2019-20 following the COVID-19 outbreak with massive disruption in business activity, the Indian equity market made a strong V-shaped recovery in H1:2020- 21. The BSE Sensex gained 46.5 per cent in H1:2020-21 after hitting a low of 25981 on March 23, 2020 (Chart IV.15a). Strong rallies in global equity markets on the back of massive fiscal and monetary stimuli in major countries and the measures are undertaken in India boosted domestic market sentiments.

The recovery continued in July and August on the back of positive news from encouraging trials of the coronavirus vaccine and hopes of more supportive measures by national authorities globally. On the domestic front, the rally in equities was also supported by improvement in the manufacturing PMI for June 2020, reports of disengagement between India and China over border issues and better than expected Q1:2020-21 corporate earnings results.

Domestic market sentiment was tempered during August by contraction in manufacturing PMI and higher-than-expected CPI inflation print for July 2020. The stock market plummeted sharply in the last trading session of the month due to fresh escalation in Indo-China border tensions and witnessed cautious trading ahead of the implementation of new trading norms on margin requirements by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) from September 1, 2020.

Investor sentiment remained insipid in September 2020 amidst concerns over a steady increase in coronavirus infections and weak global cues. After registering moderate gains due to improvement in domestic manufacturing PMI for August 2020, equity sentiments turned negative with the BSE Sensex witnessing its biggest intra-day fall in more than four months on September 24 as the spike in infections in some European countries triggered fears of a second round of lockdown. Bullish sentiments, however, returned towards the end of the month amid expectations of further stimulus measures by the government.

During H1:2020-21, FPIs turned net buyers in the Indian equity market after panic sales in March due to flight to safety. MFs, however, were net sellers to the tune of `24,801 crores during H1:2020-21. Resource mobilisation through public and rights issues of equity increased to `76,830 crores during H1:2020-21 from `60,133 crores in the corresponding period of the previous year.

Figure 4.10: Stock Market Indices and Investment

Sources: Bloomberg; NSDL; and SEBI

Foreign Exchange Market

The INR exhibited movements in both directions against the US dollar during H1:2020-21. After depreciating to its lowest level of `76.81 on April 22, 2020, the INR subsequently appreciated owing to FPI flows to the domestic equity market with the return of risk appetite for EME assets and the depreciation of the US dollar. The appreciation of the INR against the US dollar was modest as compared with EME peers.