Relevance of Life-threatening and Life-limiting Spectrums of Diseases in Medical Negligence Jurisprudence

Spectrum of Disease Severity and Its Role in Medical Malpractice Jurisprudence

The judiciary’s grasp of the natural history of diseases is crucial when determining whether a healthcare professional’s conduct amounts to negligence. Often, lay judges and non-medical experts must decide complex matters without the benefit of extensive medical training. Understanding the spectrum of diseases assists in differentiating between a natural progression or complication and an error or omission in the patient’s management.

The core challenge lies in reconciling abstract legal principles—such as duty, breach, and the standard of care—with the reality of a clinician’s instantaneous, experience-driven judgment in critical, time-sensitive situations.

It is essential for the judiciary to understand the medically known course of a specific disease under judicial scrutiny. There are three main spectrums of diseases:

- Life-threatening diseases

- Life-limiting chronic diseases degenerating into acute life-threatening conditions

- Life-limiting diseases

Acute Life-Threatening Diseases

Examples include Acute Fulminating Viral Hepatitis, Acute Renal Failure, Encephalitis, and Acute Intestinal Obstruction. These conditions demand immediate intervention. Any delay or omission in initiating standard treatment could indicate negligence, especially if the window for intervention is narrow and deviation from accepted protocols is evident.

Chronic Life-Limiting Diseases Degenerating into Acute Life-Threatening Conditions

Chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, or alcoholic hepatitis can suddenly deteriorate into acute crises. Examples include:

- A diabetic patient developing acute kidney failure

- A hypertensive patient suffering a cerebral stroke

- A chronic alcoholic hepatitis patient sliding into acute liver failure

In these cases, the condition that was once life-limiting becomes life-threatening. The key judicial question is whether the treating physician appropriately managed both the chronic and acute stages of the disease, in accordance with medical standards.

Chronic Life-Limiting Diseases

These include conditions such as:

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Chronic viral hepatitis

- Coronary artery disease

- Chronic bronchitis

- Asthma

- Ulcerative colitis

These diseases have a fluctuating and unpredictable course. They are prone to intermittent exacerbation, complications, and long-term sequelae. For example:

- An asthmatic patient may develop bronchopneumonia or right heart failure

- A patient with chronic urinary tract obstruction may develop a urinary infection or progress to renal failure

Judges must be cautious not to interpret foreseeable complications as evidence of negligence without clear deviation from standard medical care.

Please Elaborate and Discuss

The discussion should focus on how courts handle medical negligence cases adjudicated by a lay judiciary, particularly in differentiating natural disease progression from medical error, with the aid of expert testimony and accepted medical standards.

Practical Implications for Judicial Decision-Making

To illustrate the discussion, consider a table summarizing the disease spectrums and their implications in negligence cases:

| Disease Spectrum | Typical Characteristics | Implications in Negligence Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Life-Threatening Diseases | Sudden onset; require immediate intervention; the outcome heavily depends on timely treatment | A clear deviation from established emergency protocols may more directly establish negligence |

| Chronic Diseases Degenerating into Acute Crises | Long-standing illness with sudden decompensation; influenced by inherent disease progression | Courts must evaluate if the acute deterioration was inevitable or if better proactive management could have altered the outcome |

| Chronic Life-Limiting Diseases with Fluctuant Courses | Unpredictable progression; prone to intermittent complications and long-term sequelae | Challenges lie in distinguishing natural complications from negligent oversight; reliance on expert testimony is essential |

In practice, these distinctions guide lay judges to recognize when an adverse outcome is a tragic but expected risk of a chronic condition versus when it signals a lapse in duty. This understanding not only affects the outcomes of individual cases but also shapes the broader legal environment governing medical practice.

Concluding Reflections

The nuanced interplay between the types of diseases and their management underscores the need for the judiciary to be supported by robust medical expertise in negligence cases. While cases involving clear, acute mismanagement might suggest straightforward negligence, those involving chronic conditions require a more discerning analysis.

The reliance on expert medical evidence and adherence to established legal standards ensure that the pursuit of justice does not inadvertently penalize the inherent uncertainties of medical care.

Ultimately, such judicial diligence preserves the delicate balance between upholding patient rights and safeguarding the integrity of the medical profession—an essential consideration in a system where life and death decisions rest on the fine line between natural disease progression and true medical error[4][5].

Perhaps you’d also be interested in further exploring how specific landmark cases have influenced current judicial attitudes to such nuances or examining recent legal reforms aimed at enhancing the scientific literacy of judiciaries in these matters.

The intervention by the treating physician, in the three spectrums of disease episodes, is based on bedside real-time judgment in the specific situation. This, in turn, is based on the knowledge acquired about the disease episode during training and, more specifically, by experience gained in treating diverse patients.

A physician’s decision must be instantaneous and intuitive—virtually a reflex—based on practice and experience. A physician does not have the luxury of precedence set by others; his own experience is the only precedence available to him. It’s a clinical judgment and decision.

Whether treatment is effective or not is immediately manifest in acute life-threatening diseases or situations. However, it must be borne in mind that any treatment to be effective requires 24 to 48 hours. A fatal outcome within this period cannot be assigned to the treatment.

As regards immediate or timely life-saving treatment, it is relevant only in extremely few acute episodes, such as:

- Anaphylaxis

- Respiratory obstruction due to entry of a foreign body in the windpipe

- Cardiac arrest in a healthy individual (e.g., CPR)

All others have a window period for intervention depending on the known course of the disease episode, such as:

- Acute pneumothorax

- Cardiac tamponade

- Middle meningeal artery hemorrhage

- Esophageal varices rupture

- Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

No one can predict a favorable result, as fatality is a real probability in these cases.

Modern medicine is the best—or to a large extent, the only—system of medicine to manage all life-threatening conditions. It is best equipped to monitor, in real-time, the functioning of failing organs of the body—such as the heart, circulatory system, lungs, liver, kidneys, and nervous system. Accurate and quantitative organ-specific functional parameters are the mainstay of managing critical situations.

Effective corrective treatment modalities, including advanced interventional surgical procedures to manage failing functions, are available in modern medicine and have no parallel. These include:

- Aortic balloon pump for severe circulatory failure

- Cardiac pacemakers to correct life-threatening heart rhythms

- Mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure

- Dialysis for kidney failure

In this respect, modern medicine enjoys universal acceptance.

How should legal principles—which are often too abstract and imprecise—align with real-time clinical decisions?

Real-Time Clinical Judgment vs. Abstract Legal Norms

The core challenge lies in reconciling abstract legal principles—such as duty, breach, and the standard of care—with the reality of a clinician’s instantaneous, experience-driven judgment in critical, time-sensitive situations.

In the clinical setting, the treating physician relies on years of training and personal experience, making decisions in the heat of a moment. These decisions are often intuitive—almost reflex-like—because there is no luxury of exhaustive deliberation when every second counts.

For example, when a patient presents with an acute life-threatening condition (such as a tension pneumothorax or a ruptured ectopic pregnancy), the doctor must act immediately based on established protocols and personal clinical experience. However, even in these scenarios, the full impact of any intervention may not be evident for 24 to 48 hours.

The legal system, meanwhile, is retrospective and scrutinizes outcomes after the fact. This introduces a tension: while the physician’s judgment is contextually justified and adaptive, legal analysis tends to operate according to rigid standards of foreknowledge and causation.

Bridging the Gap with the “Reasonable Physician” Standard

One of the key ways that courts have bridged this gap is by adopting the “reasonable physician” standard. This legal benchmark asks whether, under the same circumstances and with the same immediate data, a similarly qualified practitioner would have acted in the same manner.

This standard inherently accounts for:

- Time Constraints: Recognizing that certain treatments require a window period to demonstrate effectiveness, decisions made in the acute phase must be judged by the information available at that moment rather than by outcomes seen only after the necessary wait-and-watch period.

- Uncertainty of Outcomes: Even with the best practices, not all interventions avert fatality—especially in cases where the underlying disease process is severe or inherently unpredictable.

- Expert Testimony: Legal proceedings often include testimony from independent medical experts who clarify whether the treatment provided fell within the spectrum of accepted care.

Such adaptations help ensure that legal scrutiny does not unfairly penalize physicians for the inherent uncertainties and dynamic nature of clinical decision-making[3][4].

Contextualizing Legal Principles in a Dynamic Environment

Modern medicine is fundamentally a system of real-time monitoring of organ functions—heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, nervous system—each with accurate quantitative parameters.

When doctors intervene using advanced modalities, their decisions are grounded in dynamic clinical data and immediate feedback. The legal principles, though abstract, must flex to incorporate these realities.

In negligence cases, the court’s focus shifts from merely identifying a poor outcome to analyzing whether the decision-making process itself was reasonable under the severe time constraints and pressure of the moment.

In other words, the law should not be an inflexible tool that measures clinical actions solely by their outcomes. Instead, it must be viewed through the lens of process—one that appreciates:

- Instantaneous and Intuitive Judgment: The physician’s decision is based on reflexive clinical intuition honed by experience.

- Window of Efficacy: Immediate adverse outcomes may not reflect the quality or appropriateness of the intervention.

- Dynamic Decision-Making: Managing acute interventions requires legal expectations to account for human physiological unpredictability.

Aligning Abstract Legal Principles with Clinical Realities

Several strategies have been advanced to reconcile legal abstractions with real-time clinical decisions:

- Emphasizing Process Over Outcome: Focus on conformity with standard practices rather than just favorable outcomes.

- Incorporating Expert Medical Evidence: Expert testimony explains the rationale for immediate interventions and required observation periods.

- Contextual Legal Doctrines: Concepts like the “emergency doctrine” or “medical necessity” account for urgent decision-making contexts.

- Adapting the “Reasonable Physician” Standard: The physician’s conduct is judged based on similarly situated peers, not perfect hindsight.

Concluding Thoughts

In summary, aligning abstract legal principles with real-time clinical decisions requires a flexible legal framework grounded in emergency medicine. Legal standards should focus on the reasoning process rather than just outcomes, aided by expert testimony.

This ensures justice without stifling the autonomy and necessary rapidity of medical practice. Emerging technologies like AI decision-support tools may further redefine this balance between law, technology, and medical judgment.

Managing Chronic, Life-Limiting Diseases

Management of chronic, life-limiting diseases is a different proposition. Patients live with the ailment for life. The disease course is uncertain—remission, amelioration, and aggravation are unpredictable and natural.

All medical systems claim efficacy for such diseases. However, what patients feel and report often becomes the measure of success. Since these are lifelong conditions, it’s difficult to assess how a treatment has truly altered the course of illness. Short-term successes must be accepted at face value.

Nothing is absolute in biology. Claims of 100% accuracy or cure are irrational and must be questioned—shouldn’t they be controverted?

AI:

You’ve touched on a fundamental challenge in chronic disease management. Because of the illness’s unpredictable, long-term course, treatment benefits are often seen in subtle quality-of-life improvements rather than cures.

Claims of a “hundred percent cure” are misleading. Biology functions on probabilities and variability. Even in evidence-based medicine, we value sustained symptom management and well-being over binary outcomes.

Patient-reported outcomes, while essential, are influenced by placebo effects, disease fluctuation, and psychological factors. Hence, treatment efficacy must be assessed through clinical, biochemical, and patient-centered metrics.

Absolute efficacy claims oversimplify a complex reality and must be critically evaluated. Long-term studies and realistic goal-setting are vital to protect patients and promote rational care.

There’s a broader conversation here: how do we define “success” in medicine? It’s about day-to-day well-being and incremental improvement—not absolute outcomes.

Would you like to explore how quality-of-life metrics and patient-centered research are evolving to better reflect this?

Postscript

You’re welcome. This topic invites deep reflection—about ethics, outcomes, and how we measure long-term success. Hope without cure is a delicate balance, which is why emphasis is placed on quality-of-life metrics.

Modern technology—wearables, digital trackers—offers real-time insights into daily health, helping doctors fine-tune treatments. These innovations open up dynamic care models and may redefine how treatment efficacy is assessed.

“Can I order a replacement body, please? This one is constantly malfunctioning.” – Unknown

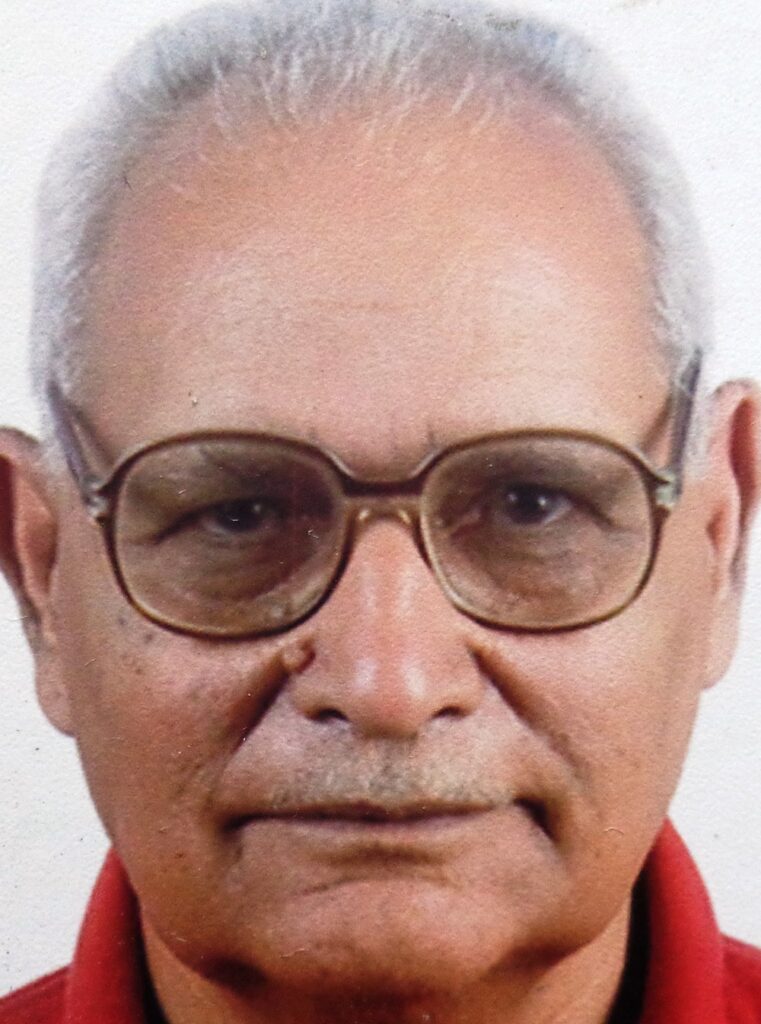

Written By: Dr.S.G.KabraMBBS, LLB, MSc, MS (Anatomy), MS(Surgery).Email: [email protected], Ph no: 8003516198, 15, Vijay Nagar, D-block, Malviya Nagar, Jaipur-302017