Hysterectomy operation performed by a trained and experienced gynecologist, following accustomed surgical norms, any iatrogenic injury to Ureter, bladder or bowel, is accidental – hence not an actionable offence.

Q. What are the reported iatrogenic injuries in ‘Hysterectomy’ in general and Laparoscopic Assisted Vaginal Hysterectomy with Salpingo-oophorectomy in particular?

AI: > Iatrogenic Injuries in Hysterectomy Procedures: A Comprehensive Analysis

Introduction

Hysterectomy remains one of the most commonly performed gynecologic surgeries worldwide, with an estimated 600,000 procedures conducted annually in the United States alone. Approaches include total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), vaginal hysterectomy (VH), laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH), and robotic-assisted hysterectomy (RH). The procedure can be completed with or without salpingo-oophorectomy, and may be assisted by laparoscopy (LAVH) or performed totally via laparoscopy (TLH).

Iatrogenic injuries—injuries inadvertently caused by surgical intervention—are a well-recognized complication of hysterectomy. These complications can affect the urinary tract (bladder and ureters), gastrointestinal tract (bowel and rectum), vasculature, and nerves, and may lead to significant morbidity if not promptly detected and managed.

This report synthesizes current evidence regarding the types, frequencies, and causes of iatrogenic injuries in hysterectomy procedures, with a special focus on laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (LAVH + BSO). The report also outlines preventive measures and recommendations to minimize these injuries.

General Hysterectomy Injuries

Urinary Tract Injuries

Urinary tract injuries are among the most frequent iatrogenic complications of hysterectomy, occurring in 0.3%–1% of gynecologic surgeries. Bladder injuries are reported in 0.5%–0.66% of cases, while ureteral injuries range from 0.02%–0.4% in LH and TLH procedures. Abdominal hysterectomy carries ureteral injury rates of 0.03%–2% and bladder injury rates of 0.2%–1.8%. Vaginal hysterectomy is associated with lower ureteral injury rates (0.9% vs. 1.7% in abdominal hysterectomy) but this risk increases to 2.6% when performed with pelvic floor reconstruction.

Common mechanisms include

- Misidentification of anatomy leading to ligation or transection of the ureter near the uterine artery or within the parametrial tunnel.

- Thermal injury from electrosurgery (monopolar or bipolar cautery), resulting in late-onset ureteral strictures or fistulae.

- Mechanical trauma during trocar or instrument insertion, especially when creating the pneumoperitoneum or during adhesiolysis.

- Delayed diagnosis — often absent until 7–10 days postoperatively — which can present with flank pain, fever, peritonitis, or urinary leakage and is associated with higher morbidity including urinary fistula and loss of renal function.

Gastrointestinal Injuries

Bowel injuries occur in approximately 0.1%–0.2% of hysterectomy cases, with the small intestine most frequently involved (47% of cases in laparoscopic gynecologic procedures).

Mechanisms include

- Trocar or Veress needle misplacement during abdominal access (up to 55% of bowel injuries).

- Thermal injury to serosa or full-thickness bowel walls from electrosurgical dissection in areas of poor visualization.

- Adhesion-related tears during blunt dissection in patients with prior surgeries or endometriosis.

- Delayed recognition — occurring in 41% of bowel injuries — can be lethal; unrecognized injuries have a mortality rate of 3.2% (five deaths in 154 delayed diagnoses).

Vascular Injuries

Although rare, vascular injuries can have catastrophic consequences. Reported incidences include:

- Major vessel laceration during trocar insertion or adhesiolysis (reported 1.3% in LH in retrospective surveys).

- Vascular injuries often involve pelvic sidewall vessels and may require immediate laparotomy, vascular repair, or transfusion.

Nerve Injuries

Peripheral nerve injuries are uncommon but can occur from patient positioning in steep Trendelenburg and lithotomy positions. Incidences range from 0.25%–2% in LH/RH procedures.

Common injuries include

- Brachial plexopathies and ulnar nerve palsies from arm abduction >90° and inadequate shoulder padding.

- Obturator and femoral nerve injuries from prolonged lithotomy position and insufficient leg support padding.

Other Complications

- Wound infection: superficial incisional infection rates of 2.3%–2.6% after abdominal hysterectomy and 0.6%–0.8% after laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Deep incisional/organ-space infection: 0.5%–1.2% across all routes, including vaginal cuff cellulitis and pelvic abscess formation.

- Febrile morbidity: 3%–50% depending on antibiotic prophylaxis and patient profile.

- Venous thromboembolism: 0.3%–1% risk of DVT or pulmonary embolism in major pelvic surgery, reduced by prophylaxis protocols.

- Vaginal cuff dehiscence: 0.14%–1.14% with higher rates in TLH, often related to early coitus and delayed healing.

- Conversion rates: 2.7%–7.5% for TLH and LAVH procedures, mainly due to adhesions or uncontrolled bleeding.

Injuries Specific to LAVH with Salpingo‑Oophorectomy

Urinary Tract Injuries in LAVH + BSO

Robotic-assisted and standard laparoscopic data reveal similar urologic injury rates:

- Robotic hysterectomy: 0.92% urologic injury rate (0.6% bladder, 0.32% ureter) in 1,088 cases.

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy: 0.90% urologic injury rate in 782 cases.

- Vaginal hysterectomy: 0.33% urologic injury rate in 304 cases.

- Open abdominal hysterectomy: 0.96% urologic injury rate in 940 cases.

Risk factors such as high BMI (>34 vs. 32) were not statistically significant for injury risk in this cohort.

Gastrointestinal Injuries in LAVH + BSO

Bowel injury rates during LAVH + BSO remain low (0.2%) with major complications often attributed to:

- Adhesiolysis in patients with prior C-sections or peritonitis.

- Thermal spread from energy devices used to control pelvic sidewall vessels.

- Immediate laparoscopic repair can be successfully performed if injuries are recognized intraoperatively.

Vascular and Nerve Injuries in LAVH + BSO

Vascular injuries during LAVH + BSO are rare (≈1.2%), but can occur during infundibulopelvic ligament division. Nerve injuries (0.4%–0.6%) are often related to steep Trendelenburg and prolonged operative times in advanced laparoscopic cases.

Case Reports and Unique Repair Techniques

Rectal perforation repair using an endoscopic stapler without diversion was reported in TLH + BSO, demonstrating feasibility when recognized intraoperatively and proper bowel preparation was performed.

Preventive Measures

Preoperative Strategies

- Risk stratification: Identify patients at high risk for urinary or bowel injury—prior C-sections, endometriosis, pelvic malignancies—using imaging (ultrasound, IVU, CT).

- Antibiotic prophylaxis: Administer cefazolin 1–2 g IV within 60 minutes of incision; re-dose for procedures >4 hours or with >1,500 mL blood loss.

Intraoperative Techniques

- Safe access: Choose open vs. closed entry based on risk factors; open Hasson technique may reduce blind trocar injuries.

- Adhesiolysis: Employ sharp dissection over blunt methods to minimize serosal tears and thermal injury in dense adhesions.

- Ureteral identification: Dissect and skeletonize the ureters early in challenging cases; use retroperitoneal landmarks.

Intraoperative Detection Techniques

- Routine cystoscopy: Perform cystoscopy after laparoscopic hysterectomy to detect 95% of unsuspected injuries; improves detection from 25%–50% to 80%–95% for bladder and ureteric lesions.

- Dye injection: Use indigo carmine (5 mg) or alternative dyes (methylene blue, sodium fluorescein, phenazopyridine) to visualize ureteral jets; alternatives carry varied risks and costs.

Training and Simulation

- Simulation labs: Incorporate commercially available models (e.g., Miya VH simulator) to teach pelvic anatomy and instrumentation steps; improved confidence and knowledge scores in residents.

- Robotic proficiency: Achieve a minimum of 25–30 proctored procedures to reduce vascular and nerve injuries in robotic-assisted surgery.

Emerging Technologies

- Fluorescence imaging: Near-infrared dyes to highlight ureters and vessels in real-time laparoscopic surgeries.

- Advanced energy devices: Vessel-sealing instruments with reduced thermal lateral spread.

Recommendations and Guidelines

- AAGL guidelines: Follow AAGL’s recommendations for intraoperative cystoscopy in laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures to optimize detection and management of urinary tract injuries.

- Classification and reporting: Employ standardized classification systems (e.g., Querleu-Morrow, AAST) to audit complications effectively and enhance data comparability across centers.

Summary Table of Key Injuries, Frequencies, and Causes

| Injury Type | Frequency | Primary Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder injury | 0.5%–1.8% | Trocar perforation, thermal injury, misidentification |

| Ureteral injury | 0.02%–2.6% | Ligation, thermal damage, anatomical proximity |

| Bowel injury | 0.1%–0.2% | Access trauma, thermal spread, adhesiolysis |

| Vascular injury | 0.5%–1.3% | Trocar insertion, deep pelvic dissection |

| Nerve injury | 0.25%–2% | Trendelenburg, arm abduction, inadequate padding |

| Superficial infection | 0.6%–2.6% | Endogenous contamination, incision handling |

| Deep organ/space infection | 0.5%–1.2% | Vaginal cuff cellulitis, abscess formation |

| Febrile morbidity | 3%–50% | Infections, VTE, GI injury |

| DVT/PE | 0.3%–1% | Immobilization, surgical stress |

| Vaginal cuff dehiscence | 0.14%–1.14% | Early intercourse, poor suturing |

Conclusion

Iatrogenic injuries in hysterectomy procedures, particularly in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with salpingo‑oophorectomy, encompass a spectrum of urinary, gastrointestinal, vascular, and neurologic complications. While minimally invasive approaches reduce some risks associated with open surgery, they introduce unique challenges requiring meticulous technique, comprehensive anatomical knowledge, intraoperative detection protocols, and dedicated surgical training.

Adoption of routine cystoscopy, simulation-based education, and evidence-based guidelines can substantially mitigate injury rates and improve patient outcomes. Ongoing research and standardized reporting remain essential for continuous improvement in gynecologic surgical safety.

Appendix — Surgical anatomy of the ureter (elaboration)

For ureteric and bladder injuries it is essential to detail the ureter’s course through the female pelvis because its vulnerability is highly site-specific. Key points:

- Ovarian fossa entry: As the ureter enters the pelvis it lies in the ovarian fossa and is closely related to the ovary. Inflammatory adhesions involving the ovary can tether the ureter and increase risk during ovarian dissection.

- Lateral pelvic wall course: The ureter descends along the lateral pelvic wall within a curtain of lymphatic tissue. During radical hysterectomy with lymph node clearance, the ureter must be mobilized (“cleaned”) along its length before node removal; this maneuver risks injury to small peri‑ureteral vessels and may lead to delayed ischemic necrosis and subsequent perforation.

- Passage under the uterine ligament: The ureter traverses beneath the thick uterine (cardinal/parametrial) ligament near the level of the internal os. Division of these supporting ligaments carries a risk of inadvertent ureteral transection if the ureter is not identified and protected.

- Relation to the vagina and bladder: The terminal ureter runs between the upper vagina/cervix and the bladder. During separation of the vagina and cervix from the bladder (cystotomy plane), both ureter and bladder are at risk of injury.

Because the risk is site-specific, each step of the surgical procedure contains inherent protective strategies to avoid inadvertent injury. These complications are uncommon and can occur despite careful technique, even in experienced hands.

Ureteric Injuries in Pelvic Surgery: Anatomy, Vulnerabilities, and Prevention

Understanding why the ureter is so easily injured during gynecologic procedures begins with a step-by-step tour of its pelvic course. Each anatomical “pinch point” carries a unique risk and demands targeted preventive tactics.

Pelvic Course and Key Relations

Crossing the Pelvic Brim

After descending along the psoas major, the ureter crosses the pelvic brim at the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels, entering the true pelvis.

Ovarian Fossa

Here the ureter lies in the ovarian fossa, passing immediately medial to the ovary and suspensory ligament. It is crossed anteriorly by the ovarian vessels as they enter the pelvis.

Lateral Pelvic Wall

It then travels inferomedially along the pelvic sidewall, weaving through the pelvic lymphatic mesh before reaching the cardinal ligament.

Cardinal (Transverse Cervical) Ligament

Approximately 1.5–2 cm lateral to the cervix, the ureter runs beneath the uterine artery—the classic “water under the bridge” relationship.

Vesicouterine Fold and Bladder Base

Finally it pierces the bladder wall at an oblique angle, creating a valve mechanism. In the vesicouterine fold it is sandwiched between the vaginal cuff and anterior bladder dome.

Site-Specific Vulnerabilities

| Site | Anatomical Risk | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ovarian Fossa | Medial location to ovary; adherent in inflammatory or endometriotic pelvis | Transection during oophorectomy or adhesiolysis |

| 2. Lateral Pelvic Wall | Embedded in lymphatic tissue; skeletonized during pelvic lymphadenectomy in radical hysterectomy | Damage to peri-ureteral vessels → delayed necrosis & perforation |

| 3. Cardinal Ligament | Hidden beneath dense ligamentous fibers; not visible until ligament is divided | Ligation or thermal injury during uterine artery control |

| 4. Vesicouterine Fold & Bladder | Interposed between cervix-vagina and bladder; vulnerable during colpotomy or bladder flap creation | Partial laceration or thermal injury to bladder or ureter |

Inherent Steps to Prevent Inadvertent Injury

Systematic Ureteral Identification

Visually trace the ureter at each site: from the pelvic brim to the bladder.

Mobilize over the psoas and follow its peritoneal reflection down into the pelvis.

Minimize Skeletonization

In lymph-node clearance, preserve as many peri-ureteral microvessels as possible to maintain segmental blood supply and prevent ischemic necrosis.

Energy-Device Caution

Keep electrosurgical dissection at least 1 cm lateral to the ureter.

Consider cold-knife division of cardinal ligaments when visibility is limited.

Adjunctive Ureteral Stenting or Visualization

In distorted anatomy (large masses, repeat surgery, severe endometriosis), intraoperative stents or real-time fluorescence (ICG dye) can highlight the ureter’s course.

Routine stenting is not required for straightforward cases, but it facilitates rapid recognition if injury occurs.

Bladder Mobilization Protocol

Before creating the bladder flap, fill the bladder with saline (± methylene blue) to confirm its inferior margin.

Dissect in the correct plane between the vesicouterine peritoneum and bladder wall.

Summary Table of Risk and Prevention

| Vulnerable Segment | Risk Factor | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Fossa | Inflammatory adhesions around ovary | Sharp dissection; gentle traction on suspensory ligament |

| Lateral Wall (LNs) | Lymphadenectomy skeletonizing peri-ureteral tissue | Limit skeletonization; use vessel-sparing techniques |

| Cardinal Ligament | Hidden ureter under uterine artery | “Water under the bridge” check; cold-knife division |

| Vesicouterine Fold & Bladder | Loss of bladder flap plane landmarks | Bladder filling test; methyl blue dye injection |

Mastering these anatomy-driven safeguards transforms ureteral protection from reactive identifications into proactive prevention. With deliberate recognition of each high-risk zone—paired with meticulous dissection and adjunctive visualization techniques—iatrogenic ureteral and bladder injuries can be reduced even in the most complex pelvic surgeries.

Q. Guidelines to prevent iatrogenic injuries to Ureter and Urinary bladder in hysterectomy surgeries?

Guidelines to Prevent Iatrogenic Ureter and Bladder Injuries during Hysterectomy

Preoperative Planning

Surgeon must have a thorough knowledge of the location of the ureter during various pelvic procedures and the specific regions where it is most susceptible to injury.

Preoperative ureteral catheterization has long been proposed as a technique to identify the ureters and avoid iatrogenic injury in high-risk cases.

Intraoperative Techniques

Identify and mobilize the ureter early in the dissection. Skeletonize the uterine arteries at their origin to maintain a safe distance from the ureteric course.

Use sharp dissection to create a bladder flap and avoid thermal spread within 1 cm of the ureter or bladder wall. Urinary tract damage can result from laceration, ligation, or thermal injury if energy devices are misapplied.

Routinely inspect bladder integrity by filling with saline or diluted methylene blue; any extravasation signals a bladder tear requiring immediate repair.

Perform operative cystoscopy at the end of hysterectomy to inspect bladder mucosa and ureteric orifices. Early detection through cystoscopy allows immediate repair of bladder or ureteric injuries, preventing fistula formation and renal compromise.

Postoperative Assessment

Although rare, bladder injuries occur in 0.24 % of benign and up to 3.7 % of oncologic gynecologic surgeries, while ureteral injuries range from 0.08 % to 1.1 % depending on the procedure type. Vigilant monitoring for hematuria, flank pain, decreased urine output, and fever is essential for early recognition.

If injury is suspected, obtain imaging such as ultrasound or CT urography promptly. Early diagnosis facilitates minimally invasive repair and reduces long-term morbidity.

Emerging Techniques and Future Directions

Near-infrared fluorescence with indocyanine green can highlight ureteral anatomy intraoperatively, improving real-time visualization in laparoscopic and robotic cases.

Preoperative 3D reconstruction and virtual reality simulation help surgeons anticipate anatomical variations, especially in cases with endometriosis or prior pelvic surgery.

Artificial intelligence–driven image segmentation holds promise for automated identification of ureters and bladder boundaries, guiding dissection and reducing human error.

Structured surgical training programs incorporating these technologies can shorten the learning curve and standardize prevention strategies across institutions.

· AI: > Template to draft a reply to allegation of causing injury to Ureter and Urinary bladder by negligence in performing a hysterectomy operation

A trained gynecologist is aware of vulnerability of injury to Ureter in hysterectomy procedures. Precautions to avoid injury to the Ureter and the Urinary Bladder are integrated part of the procedure. An experienced gynaecologist has avoided these injuries in dozens or hundreds of the hysterectomies done by her. An injury to Ureter or Urinary bladder at the hands of a trained and experienced surgeon performing the same standard procedure can only be by accident. Please substantiate.

· Guidelines to prevent iatrogenic injuries to Ureter and Urinary bladder in hysterectomy surgeries?

Q.A trained gynecologist is aware of vulnerability of injury to Ureter in hysterectomy procedures. Precautions to avoid injury to the Ureter and the Urinary Bladder are integrated part of the procedure. An experienced gynaecologist has avoided these injuries in dozens or hundreds of the hysterectomies done by her. An injury to Ureter or Urinary bladder at the hands of a trained and experienced surgeon performing the same standard procedure can only be by accident. Please substantiate.

AI: > Substantiation: Ureter and Bladder Injuries as Inherent, Accidental Complications

- Low Incidence of Ureter and Bladder Injuries Ureteric injuries during hysterectomy are well-recognized inherent risks due to the close anatomic relationship between the female genital tract and ureter. Large series report ureteric injury rates between 0.03% and 1.5% across all hysterectomy routes. Bladder injuries, while somewhat more common, occur in approximately 1.0% of laparoscopic hysterectomies and under 1% of open procedures when performed by experienced surgeons2.

- Persistent Residual Risk Despite Precautions Even with meticulous technique—early ureteral identification, skeletonization of uterine vessels, sharp dissection of the bladder flap, routine cystoscopy—no protocol can reduce the risk to zero. In minimally invasive approaches, contemporary data place ureteric injury incidence at 0.02%–0.4%, reflecting the tail of the learning curve even among skilled operators. Bladder injury rates similarly decline with experience but never vanish entirely: one series showed a drop from 1.0% in the first 40 cases to 0.4% after 100 procedures, underscoring a small but constant accident rate driven by anatomic variation and tissue factors2.

- High Rate of Unrecognized Intraoperative Injuries A substantial proportion of ureteric injuries elude detection during the index surgery—up to 62% are diagnosed only post-operatively, despite standard leak testing or cystoscopy. This lack of intraoperative recognition highlights that such injuries can occur unpredictably, without any breach of technique, and become apparent only as delayed complications.

- Legal Principle: Complication Versus Negligence Under established medico-legal standards (Bolam/Bolitho), a known complication occurring within accepted incidence rates—after proper consent and adherence to standard precautions—does not constitute negligence. When a trained, experienced gynecologist, who has safely performed hundreds of hysterectomies, encounters a ureter or bladder injury, the event must be classified as an accident inherent to the procedure rather than proof of deficient care.

Template: Reply to Allegation of Ureter and Bladder Injury in Hysterectomy

Below is a structured, ready-to-use template for replying to a complaint alleging negligent injury to the ureter and urinary bladder during a hysterectomy. Adapt bracketed placeholders to your case facts, court, and parties involved.

In The [Name Of Court/Forum]

Civil Suit/Complaint No. [●] of [Year]

[Name of Complainant] …Complainant

v.

[Name of Doctor/Hospital] …Respondent

Preliminary

- This Reply is filed on behalf of the Respondent, Dr. [Full Name], resident at [Address], who denies each and every allegation of negligence save as specifically admitted herein.

- At all material times, the Respondent was duly qualified (MBBS, MS [Obst & Gynae]) and possessed valid registration with the Medical Council of [State] (Regn. No. [●]).

Statement of Facts

- On [Date], the Complainant, Mrs. [X], presented with [clinical indication: e.g., fibroid uterus].

- Prior to surgery, the Respondent:

- Explained diagnosis, risks, and alternatives in vernacular/Hindi/English.

- Secured informed consent (see Annexure A).

- A standard abdominal/vaginal/laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed on [Date] under general/spinal anesthesia.

- Intraoperatively, dissection and identification of the ureter and bladder landmarks were done in accordance with standard textbooks (e.g., Williams Obstetrics, Te Linde’s Atlas).

- Postoperatively, the patient developed [signs: hematuria/flank discomfort], imaging was ordered, and a minor ureteric/bladder leak was detected.

Defenses

- Negligence Denied. The Respondent exercised due care, skill, and judgment in keeping with accepted medical standards. Any injury was a recognized risk, disclosed and consented to.

- Complication vs. Negligence. A ureteric or bladder injury is a known complication of hysterectomy (incidence 0.08–1.1% for ureter; 0.24–3.7% for bladder). Complications do not ipso facto amount to negligence.

- Standard of Care.

- Operative notes (Annexure B) show meticulous identification of ureter.

- Energy devices were used >1 cm from critical structures.

- Intraoperative cystoscopy was performed, or leak test done, as per institutional protocol.

- Contributory Factors.

- Dense adhesions from previous surgery/endometriosis (operative report at ¶[B●]).

- Patient’s BMI/comorbidities (documented in Annexure C).

- Expert Opinion. An independent consultant (Dr. [Name], Annexure D) confirms the Respondent’s conduct met the Bolam/Bolitho test.

Legal / Substantive Provisions

- Consumer Protection Act, 2019

- No deficiency in service: bona fide medical complication beyond the Respondent’s control.

- Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct) Regulations

- Duties of disclosure and consent duly fulfilled (Regulation 2.1.1).

- Burden of Proof. The Complainant bears the onus to prove breach of duty and causation beyond the admitted risk.

Prayer

In view of the above, the Respondent respectfully prays that this Hon’ble Forum may be pleased to:

- Dismiss the Complaint with costs;

- Hold that no negligence or deficiency in service has been committed;

- Award costs of expert fees and other incidental expenses;

- Pass any such other order as it may deem fit.

Date: [Date]

Place: [City]

Respectfully submitted,

Advocate for Respondent

[Name of Counsel], [Enrolment No.]

[Address, Phone, Email]

Annexures

- Copy of Informed Consent Form

- Operative Notes & Discharge Summary

- Preoperative Investigations & Comorbidity Chart

- Expert Opinion (Bolam/Bolitho Compliance)

- Intraoperative Cystoscopy/Leak Test Report

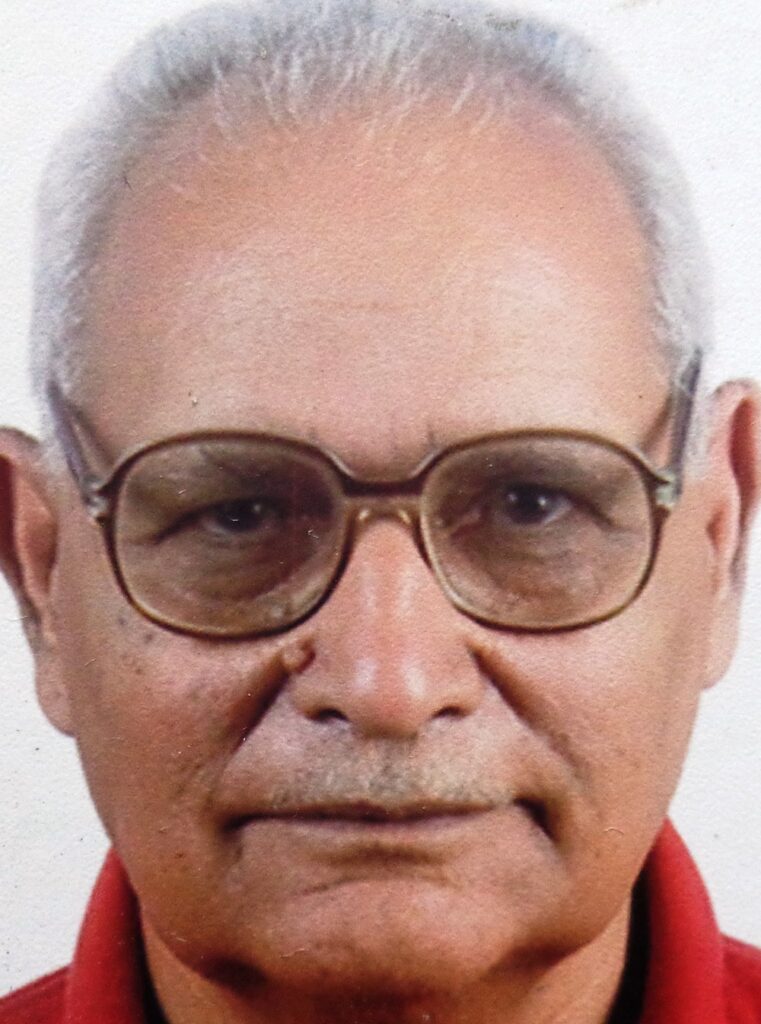

Written By: Dr Shri Gopal Kabra

MBBS, LLB, MSc, MS(Anatomy), MS(Surgery)

Email: [email protected] Mobile: 8003516198